Mysterious Vaping Lung Injuries May Have Flown Under Regulatory Radar (KHN)

Sydney Lupkin, Kaiser Health News and Anna Maria Barry-Jester It was the arrival of the second man in his early 20s gasping for air that alarmed Dr. Dixie Harris. Young patients rarely get so sick, so fast, with a severe lung illness, and this was her second case in a matter of days. Then she saw three more patients at her Utah telehealth clinic with similar symptoms. They did not have infections, but all had been vaping. When Harris heard several teenagers in Wisconsin had been hospitalized in similar cases, she quickly alerted her state health department. As patients in hospitals across the country combat a mysterious illness linked to e-cigarettes, federal and state investigators are frantically trying to trace the outbreaks to specific vaping products that, until recently, were virtually unregulated. As of Aug. 22, 193 potential vaping-related illnesses in 22 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wisconsin, which first put out an alert in July, has at least 16 confirmed and 15 suspected cases. Illinois has reported 34 patients, one of whom has died. Indiana is investigating 24 cases. Lung doctors said they had seen warning signs for years that vaping could be hazardous, as they treated patients. Medically it seemed problematic, since it often involved inhaling chemicals not normally inhaled into the lungs. Despite that, assessing the safety of a new product storming the market fell between regulatory cracks, leaving doctors unsure where to register concerns before the outbreak. The Food and Drug Administration took years to regulate e-cigarettes once a court determined it had the authority to do so. “You don’t know what you’re putting into your lungs when you vape,” said Harris, a critical care pulmonologist at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City. “It’s purported to be safe, but how do you know if it’s safe? To me, it’s a very dangerous thing.” Off The Radar When electronic cigarettes came to market about a decade ago, they fell into a regulatory no man’s land. They are not a food, not a drug and not a medical device, any of which would have put them immediately in the FDA’s purview. And, until a few years ago, they weren’t even lumped in with tobacco products. As a result, billions of dollars of vaping products have been sold online, at big-box retailers and in corner stores without going through the FDA’s rigorous review process to assess their safety. Companies like Juul, Blu and NJoy quickly established their brands of devices and cartridges, or pods. And thousands of related products are sold, sometimes on the black market over the internet or beyond. “It makes it really tough because we don’t know what we’re looking for,” said Dr. Ruth Lynfield, the state epidemiologist for Minnesota, where several patients were admitted to the intensive care unit as a result of the illness. She added that if it turns out that the products in question were sold by unregistered retailers and manufacturers “on the street,” outbreak sleuths will have a harder time figuring out exactly what is in them. With e-cigarettes, people can vape — or smoke — nicotine products, selecting flavorings like mint, mango, blueberry crème brûlée or cookies and milk. They can also inhale cannabis products. Many are hopeful that e-cigarettes might be useful smoking cessation tools, but some research has called that into question. The mysterious pulmonary disease cases have been linked to vaping, but it’s unclear whether there is a common device or chemical. In some states, including California and Utah, all of the patients had vaped cannabis products. One or more substances could be involved, health officials have said. The products used by several victims are being tested to see what they contained. Because e-cigarettes aren’t classified as drugs or medical devices, which have well-established FDA databases to track adverse events, doctors say there has been no clear way to report and track health problems related to vaping products. And this has apparently been the case for years. Multiple doctors described seeing earlier cases of severe lung problems linked to vaping that were not officially reported or included in the current CDC count. Dr. Laura Crotty Alexander, a pulmonologist and researcher with the University of California-San Diego, said she saw her first case about two years ago. A young man had been vaping for months with the same device but developed acute lung injury when he switched flavors. She strongly suspected a link, but did not report the illness anywhere. “It wasn’t that I didn’t want to report it, it’s that there’s no pathway” to do so, Alexander said. She said she’s concerned that many physicians haven’t been asking patients about e-cigarette use and that there’s no way to document a case like this in the medical coding system. Dr. John E. Parker of West Virginia University said he saw his first patient with pneumonia tied to vaping in 2015. Doctors there were intrigued enough to report on the case at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Parker and his team didn’t contact a federal agency, and Parker said it was unclear whom to call. Numerous other cases have been reported in medical journals and at professional conferences in the years since. The FDA’s voluntary system for reporting tobacco-related health problems included 96 seizures and only one lung ailment tied to e-cigarettes from April through June of this year. The system appears to be utilized most by concerned citizens, rather than manufacturers or health care professionals. But several lung specialists said that due to the patchwork nature of regulatory oversight over the years, the true scope of the problem is yet to be identified. “We do know that e-cigarettes do not emit a harmless aerosol,” said Brian King, a deputy director in the Office on Smoking and Health at the CDC in a call with media on Aug. 23 about the outbreak. “It is possible that some of these cases were already occurring but we were

Having a Baby While Working as a Travel Nurse

By Alex McCoy, Contributing Writer, Owner of Fit Travel Life I don’t know if it is Facebook reading my mind or just a coincidence but I have been seeing more and more posts in travel healthcare groups addressing the issue of children and traveling. Questions range from having babies and taking maternity leave while traveling to how to travel with older children while homeschooling. I am currently pregnant with baby number one and can tell you that working as a travel nurse did not deter our decision to start a family–in fact, it made the idea a little less daunting and exciting! We are looking forward to traveling with a baby and continuing to save for a home, a new car and retirement even with the added expense of a little one. While we haven’t had to actually deal with childcare or homeschool just yet, I do have several friends who travel with older children and will share some of the tips I have learned from them about those stages of parenting on the road. Before baby: have a plan for where you want to deliver Ultimately you can receive prenatal care anywhere you can find an obstetrician or midwife. My husband and I decided to deliver at home, so we saw a midwife for the first 20 weeks and then transferred care to my physician back home. All it took was a few medical release forms and some phone calls to coordinate the switch, and my medical care picked right up where it had left off. For insurance: decide if you want to use COBRA or private insurance As a female I will obviously not be working a contract right when I deliver, so my company insurance would lapse in that time frame. Our family’s option was to put me on my spouse’s insurance and figure out a way to coordinate him getting time off when the baby arrives, or to have both of our jobs finish up before baby and opt to use COBRA during the lapse in insurance. COBRA is more expensive than insurance through a company, so you just have to plan for this expense ahead of time. Another option is to carry private insurance. Depending on your state costs will vary, and you may not be eligible to sign up for private coverage if it isn’t open enrollment. If you are in the early stages of planning a family you may have more time to coordinate this and get benefits in place before conceiving if that is what you prefer. Coordinate your contracts, or take a permanent job temporarily. I have talked to some parents who chose to simply end their last contract around the 37 or 38-week mark and then travel to their chosen delivery spot and take some time off before the baby arrives. We personally decided to take permanent jobs close to home so we could have steady insurance and some time to adjust to life as parents before hitting the road again. We didn’t necessarily tell our employers our plans, but we both took jobs we knew we could be happy at for six months to a year and we will reassess at that point. The benefit of working a contract is you can then take as much time off as you would like to bond with the baby. If you are a new employee it may be trickier to coordinate leave depending on your state laws governing maternity leave. I have learned a lot about federal regulations in this area, and unfortunately, it is up to the state to determine if you get more than the medically necessary six weeks off guaranteed. After baby: childcare options. One of the most daunting tasks as a soon to be a parent is deciding how to find care for your baby if you decide to work full time once they arrive. As travelers, this can get even trickier because you are moving frequently so you can’t use the same caregiver the entire time. While we haven’t faced this issue yet, if we both decide to work contracts at the same time we would most likely look into hiring a private nanny. My friends Steve and Ellen over at PTAdventures travel with their toddler and elected to take positions in areas where they could work for a year or longer to help create more normalcy for their little one. This is a great option that we will probably look into when we get to that point. Deciding to take the leap into parenthood (or being surprised by it) can be a scary time full of unknowns for any person. So many people talk about having babies in regards to how limiting it is which makes traveling with a baby seem impossible. Like anything else, however, I truly believe your attitude towards the situation is what will determine how successful you can be. There is a newly added level of flexibility that comes into play, but having a baby and then traveling with a baby can be a great way to show your child all that our beautiful country has to offer while setting your family up for financial success long term. Alex McCoy currently works as a pediatric travel nurse. She has a passion for health and fitness, which led her to start Fit Travel Life in 2016. She travels with her husband, their cat, Autumn and their dog, Summer. She enjoys hiking, lifting weights, and trying the best local coffee and wine. << Travel Nurse Spotlight: Taking on New Adventures Across the Country

Travel Nurse Spotlight: Stories and Insights from a 10-Year Traveler

Healthcare travel is complex and can be challenging to navigate, especially for first-time travelers. From finding the right recruiter to understanding pay packages and reviewing contracts, travel nurses need to be well-educated. Seasoned traveler and ER nurse, Lisa D., wishes there was a better platform for new travelers to learn the ins and outs of the industry. Traveling for nearly 10 years and completing more than 25 assignments, Lisa shares her stories, experiences and important things travel nurses need to know. “There are positive sides and negative sides to travel nursing; travelers need to know both sides,” Lisa said. “My persona is: you can do anything for 13 weeks. If you don’t like a facility, it’s only 3 days a week for 13 weeks.” Lisa began her nursing career as an LPN in the ER, which also landed her an EMT first responding position with her local fire department. When her two children went to college, so did she to get her Registered Nursing license. Once a RN and a soon-to-be empty nester, she started working toward her two years of experience required to travel by doing local contracts, helping nearby hospitals with staffing shortages. For example, she filled in for a nurse who was deployed in the military. Early in her travel RN career, Lisa had a unique opportunity to work a 4-week assignment in Hawaii, which she said was an eye-opening experience. It was at a very small ER department with disordered room numbers and dated processes, but she stayed open-minded. She was frequently floated to the 6-patient ICU, because other ER nurses weren’t as willing to. “The staff nurses loved me and I enjoyed helping out,” Lisa said. “I’m from the ER, I’m used to having a lot more patients at a time. When they apologized for having to give me another ICU patient, I was like ‘sure, give me another one!’ with a smile.” The best part of her assignment in Hawaii, she bought her children and their significant others plane tickets for Christmas, and they had a week exploring the beautiful island with her. Lisa’s positive attitude, adaptability and willingness to help in any situation is what facilities look for in great travel nurses. Lisa’s biggest and most important piece of advice: like your healthcare recruiter. “Get a recruiter you can count on and enjoy talking to,” Lisa said. “If you don’t feel warm and fuzzy with your recruiter, go talk to other recruiters until you find one with the right niche. There are tons of other companies out there to choose from.” Lisa has worked with about six different staffing agencies, two of which she said she will never work with again because of recruiter issues. The most important qualities she values in a recruiter are knowledge and honesty. “Don’t be afraid to ask questions, especially when you’re new to the game,” Lisa said. “Make sure you have all of the facts. If something looks off on your contract, tell them.” Lisa’s biggest pet peeve is recruiters not answering her questions. At one hospital, she was faced with a difficult assignment and unsafe working conditions. She feared for her license and expressed her concerns to her recruiter, who shrugged it off and told her, “don’t worry about it.” Another assignment, she was promised a completion bonus, but had to fight for it. The company’s reasoning was they had changed their pay schedule and tried to move the end date mid-contract without her permission. She knew they couldn’t change the contract without her agreement. Unfortunately, newer travelers may not know how to handle these types of situations like she did. How do you research what healthcare staffing companies to work with? Lisa shares her top tips: Research who likes the company or recruiter and, most importantly, why they like them. Get on Facebook (company pages, reviews, travel groups). Know the sites you can trust and the sites you can’t (i.e. if a travel nursing review site only publishes positive reviews, they probably are hiding the negative ones). Take note of who calls you and when. For example, Lisa only works day shift and tells recruiters this. If they keep calling about night positions, they aren’t listening or putting the traveler’s best interest first. Know your pay range and look for a company who has pay packages to accommodate. Talk with travelers you work with! Lisa’s Golden Rule: if a recruiter doesn’t know the answer to a question, they should tell you truthfully that they don’t know, but they will find out for you! And that is just the supportive attitude that Lisa has found with her current recruiter. “Lisa is an absolute pleasure to work with,” said her talent advisor Leah Moss. “She has a great attitude and is always willing to help others any chance she can. I enjoy hearing about her travel stories, and appreciate her sincerity and passion for nursing.” “Everyone has their reasons to travel,” Lisa said. “My reason, I don’t do vacations very well, so travel nursing is like my vacation for 13 weeks. Working only three days a week, the other four days are vacation where I can go explore.”

A Young Woman, A Wheelchair And The Fight To Take Her Place At Stanford (KHN)

Jenny Gold, Kaiser Health News Photos by Heidi de Marco OAKLAND, Calif. — Sylvia Colt-Lacayo is 18, fresh-faced and hopeful, as she beams confidence from her power wheelchair. Her long dark hair is soft and carefully tended, and her wide brown eyes are bright. A degenerative neuromuscular disease, similar to muscular dystrophy, has left her with weak, underdeveloped muscles throughout her body, and her legs are unable to support any weight. Each time she needs to get in or out of her wheelchair — to leave bed in the morning, use the bathroom, take a shower, change clothes — she needs assistance. Throughout her young life, Sylvia has been told her disability didn’t need to hold her back. And she took those words to heart. She graduated near the top of her high school class in Oakland with a 4.25 GPA. She was co-captain of the mock trial team at school, served on the youth advisory board of the local children’s hospital, interned in the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office and is a budding filmmaker. In April, Sylvia learned she had been admitted to Stanford University with a full scholarship for tuition, room and board. To move out of her family home and into a dorm, her doctor determined she would need at least 18 hours of personal assistance each day to help with the daily tasks typically done by her mother. As she began to research options, Sylvia came to a startling conclusion: Despite the scholarship, her family wouldn’t be able to afford the caregiver hours she would need to live on campus. And she would learn in coming months that she was largely on her own to figure it out. Over the past several decades, medical advances have allowed young people with disabilities to live longer, healthier lives. But when it comes time to leave home, they run up against a patchwork system of government insurance options that often leave them scrambling to piece together the coverage they need to survive. “On paper I did everything right,” said Sylvia. “You get into this school, they give you a full ride; but you still can’t go, even though you’ve worked so hard, because you can’t get out of bed in the morning. It’s mind-boggling.” People with serious disabilities face a frustrating conundrum: Federal and state insurance will pay for them to live in a nursing home, but if they want to live in the community, home-based care is often underfunded. “We have an institutional bias in this country,” said Kelly Buckland, executive director of the National Council on Independent Living. “The bias is that if you become disabled or old, you need to go someplace else. You need to go to an institution.” Across the country, Buckland said, hundreds of thousands of adults with disabilities could thrive in a community setting if they were able to get the assistance they needed. Because Sylvia is under 21, the laws are more generous. Federal law requires states to cover much of the care that she needs to live independently. But the system is fragmented and varies by state, making it difficult even for young people to secure the necessary services. And once Sylvia reaches 21, Medicaid coverage of home and community-based care is optional for states. Most, including California, offer some coverage, but even states with broad coverage usually limit the hours they will pay for, or have waiting lists that can stretch years. The ‘Pee Math’ Calculation Sylvia’s mom, Amy Colt, has been her daughter’s caregiver from the time she was born, alongside her full-time job as a teacher. It’s a strenuous job, requiring both brawn and delicacy. As Sylvia has gotten older, she naturally has added weight and height and her muscles have become progressively weaker, making the job of caring for her ever more challenging. Amy, 57, recently started physical therapy in the hopes of maintaining the agility she needs to help her daughter, even as she herself ages and begins to lose strength. Sylvia’s parents are divorced, and while her father is an active part of her life, he does not take part in her daily caregiving needs. Every morning, Amy begins by lifting Sylvia to a seated position on the bed. She wraps her arms around her daughter below her armpits, hoists her up and pivots her carefully into her wheelchair. Sylvia helps as much as she can by holding onto her mother’s shoulders and trying to bear some weight on her toes, but it isn’t much. As her mother carries her, Sylvia’s legs hang down like sandbags, heavy and limp. She has more strength in her upper body and is able to complete tasks like eating, brushing her teeth and doing her makeup independently. In the bathroom, Amy lifts Sylvia to the toilet, then the shower. To help her dress, Amy moves Sylvia back onto the bed and rolls her side to side, shimmying her pant legs on a little bit at a time. It’s a grueling process, and one that needs to be repeated every time Sylvia uses the bathroom. That plays into something Sylvia calls her “pee math”: She avoids drinking water between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. so she does not have to use the restroom at school. She plans to continue the practice at Stanford, to cut down on aide hours. Sylvia still will need help mornings and evenings, not only with bathing and dressing, but also with laundry and cleaning her room. She expects she’ll need to employ somewhere between six and 15 aides, overseeing their schedules and payments. In a city as expensive as Palo Alto, it can be challenging to find caregivers willing to work for the $14 an hour paid by Medi-Cal. “Stanford is going to be a culture shock academically. And then she’s going to have to hire and monitor a company of employees,” Amy worries. “That’s going to be a full-time job.” Still, Sylvia is ready to leave home. So, she applied for Medicaid,

To Save Money, American Patients And Surgeons Meet In Cancun (KHN)

Phil Galewitz, Kaiser Health News CANCUN, Mexico — Donna Ferguson awoke in the resort city of Cancun before sunrise on a sweltering Saturday in July. She wasn’t headed to the beach. Instead, she walked down a short hallway from her Sheraton hotel and into Galenia Hospital. A little later that morning, a surgeon, Dr. Thomas Parisi, who had flown in from Wisconsin the day before, stood by Ferguson’s hospital bed and used a black marker to note which knee needed repair. “I’m ready,” Ferguson, 56, told him just before being taken to the operating room for her total knee replacement. For this surgery, she would not only receive free care but would receive a check when she got home. The hospital costs of the American medical system are so high that it made financial sense for both a highly trained orthopedist from Milwaukee and a patient from Mississippi to leave the country and meet at an upscale private Mexican hospital for the surgery. Ferguson gets her health coverage through her husband’s employer, Ashley Furniture Industries. The cost to Ashley was less than half of what a knee replacement in the United States would have been. That’s why its employees and dependents who use this option have no out-of-pocket copayments or deductibles for the procedure; in fact, they receive a $5,000 payment from the company, and all their travel costs are covered. Parisi, who spent less than 24 hours in Cancun, was paid $2,700, or three times what he would get from Medicare, the largest single payer of hospital costs in the United States. Private health plans and hospitals often negotiate payment schedules using the Medicare reimbursement rate as a floor. Ferguson is one of hundreds of thousands of Americans who seek lower-cost care outside the United States each year, with many going to Caribbean and Central American countries. A key consideration for them is whether the facility offers quality care. In a new twist on medical tourism, North American Specialty Hospital, known as NASH and based in Denver, has organized treatment for a couple of dozen American patients at Galenia Hospital since 2017. Parisi, a graduate of the Mayo Clinic, is one of about 40 orthopedic surgeons in the United States who have signed up with NASH to travel to Cancun on their days off to treat American patients. NASH is betting that having an American surgeon will alleviate concerns some people have about going outside the country, and persuade self-insured American employers to offer this option to their workers to save money and still provide high-quality care. NASH, a for-profit company that charges a fixed amount for each case, is paid by the employer or an intermediary that arranged the treatment. “It was a big selling point, having an American doctor,” Ferguson said. The American surgeons work closely with a Mexican counterpart and local nurses. NASH buys additional malpractice coverage for the American physicians, who could be sued in the United States by patients unhappy with their results. “In the past, medical tourism has been mostly a blind leap to a country far away, to unknown hospitals and unknown doctors with unknown supplies, to a place without U.S. medical malpractice insurance,” said James Polsfut, the chief executive of NASH. “We are making the experience completely different and removing as much uncertainty as we can.” Medical tourism has been around for decades but has become more common in the past 20 years as more countries and hospitals around the world market themselves to foreigners. There are, of course, risks to going outside the country, including the headache of travel and the possibility that the standards of care may be lower than at home. If something goes wrong, patients will be far from family and friends who can help — and it might be more difficult to sue providers in other countries. Chasing Lower Costs The high prices charged at American hospitals make it relatively easy to offer surgical bargains in Mexico: In the United States, knee replacement surgery costs an average of about $30,000 — sometimes double or triple that — but at Galenia, it is only $12,000, said Dr. Gabriela Flores Teón, medical director of the facility. The standard charge for a night in the hospital is $300 at Galenia, Flores said, compared with $2,000 on average at hospitals in the United States. The other big savings is the cost of the medical device — made by a subsidiary of the New Jersey-based Johnson & Johnson — used in Ferguson’s knee replacement surgery. The very same implant she would have received at home costs $3,500 at Galenia, compared with nearly $8,000 in the United States, Flores said. Galenia is accredited by the international affiliation of the Joint Commission, which sets hospital standards in the U.S. But to help doctors and patients feel comfortable with surgery here, NASH and Galenia worked to go beyond those standards. That included adding an extra autoclave to sterilize instruments more quickly, using spacesuit-like gowns for doctors to reduce infection risk and having patients start physical therapy just hours after knee- or hip-replacement surgery. I. Glenn Cohen, a law professor at Harvard and an expert on medical tourism, called the model used by NASH and a few other similar operations a “clever strategy” to attack some of the perceived risks about medical tourism. “It doesn’t answer all concerns, but I will say it’s a big step forward,” he said. “It’s a very good marketing strategy.” Still, he added, patients should be concerned with whether the hospital is equipped for all contingencies, the skills of other surgical team members and how their care is handed off when they return home. Officials at Ashley Furniture, where Ferguson’s husband, Terry, is a longtime employee, said they had been impressed so far. The company offers the option of overseas surgery through NASH at no cost — and with an incentive. “We’ve had an overwhelming positive reaction from employees who have gone,” said Marcus Gagnon, manager of global benefits

Can You Switch Specialities as a Traveler?

By Alex McCoy, Contributing Writer, Owner of Fit Travel Life You have finally made it. You hit the coveted two years working as a nurse and are able to start applying for your first travel job. Maybe, just maybe this will be the answer to the nagging burnout you are already starting to feel. After two years of hospital politics, difficult patient loads, and too much overtime you are ready to hit the road and see what other facilities have to offer. After two or three contracts it finally hits you–maybe it isn’t just your staff job that was the problem. Instead, you realize that your particular specialty just isn’t the right fit for your personality. Travel nursing may help with some of this internal stress, but ultimately your curiosity about your dream specialty is still there. There is just one problem. The only way to actually stop and start again in a new specialty is to hit pause on travel nursing for the time being. Hang up your travel shoes for a year or more and try to score a job in the new specialty. Which also entails giving up travel pay, extra time off, and the general adventure that travel nursing has to offer. This can be a devastating decision for many nurses to make. Inevitably it leads many to ask the question: do I really have to stop traveling to switch specialties or can I find a way to do it while traveling? The short answer to this question is: maybe. Many seasoned travelers will tell you there is absolutely no way to switch to a new specialty as a nurse without taking a permanent job for a minimum of one year before going back to a travel assignment. But every once in a while an opportunity may come along that proves them wrong. In certain situations, travelers will have the opportunity to be hired into an area they may be unfamiliar with. This usually happens when a facility is particularly desperate to get a traveler hired ASAP and leadership is willing to compromise by offering a little extra orientation time in exchange. Most commonly I have seen this happen between critical care and procedural areas. For example, ICU nurses who are familiar with vents and drips may encounter opportunities to cross-train to a procedural area like Interventional Radiology because management feels that people with those critical care skills will have an easier time learning the procedural side. I have also seen opportunities for critical care areas like ER and ICU offer extra training to nurses from the opposite specialty. Chances are the worst ER patients will be something an ICU nurse is familiar with, and an ER nurse has the training to manage most of the medications and interventions happening in an ICU, just in a slightly different setting. While these opportunities may come along every once in a while, they are not a guarantee that you would be competent enough to change specialties after a 13-week assignment. In many situations where they offer to less experienced travelers to a new specialty, the facility may only have time to train the new staff to take care of the less acute patients. By offloading even the “easier” patients this allows them to have more experienced staff free to take the more complicated patients. Because they can’t offer a full orientation period there may simply not be enough time to learn all you would need to to become a fully qualified traveler in that specialty. There may be ways to still use this to your advantage. If the opportunity arises to extend your contract, consider asking for a few extra orientation shifts during your extension so you can care for a bit more critical patients. You may also find that they will gradually increase the acuity of your patients as you gain confidence in your new area. In the event that you stay 6 or more months in a job willing to cross-train, you may gain enough experience to feel confident traveling in the new specialty. On the other hand, getting a taste of this new specialty could be a great tool to help you decide if it is really a good fit. Rather than committing to a full-time job and stopping travel altogether, getting the opportunity to try a new setting for three months could be helpful in at least eliminating that area from your list of potential future jobs if nothing else. This was my experience when I had the opportunity to cross-train to a case management position. It was in a dream location and had great pay, so I jumped on the opportunity to try something new. After thirteen weeks I was so thankful I had not committed to that type of position in a full-time job and was able to move along and be thankful for the chance to realize this before I felt stuck in a permanent job. Many people will refer to opportunities to learn a new specialty as a “unicorn” assignment–meaning the chance to snag them may be few and far between. If changing specialties is on your mind but quitting travel is not, I highly recommend discussing this with your recruiter so they know if a job like this comes across their desk you are the person to reach out to. As with anything in travel nursing, stay flexible and don’t be afraid to try something new if the little voice inside your head is saying it might be a good fit. After all, in the end, it is still only thirteen weeks. Alex McCoy currently works as a pediatric travel nurse. She has a passion for health and fitness, which led her to start Fit Travel Life in 2016. She travels with her husband, their cat, Autumn and their dog, Summer. She enjoys hiking, lifting weights, and trying the best local coffee and wine. << What I Would Change if I Could Reset My Travel Nursing Career

Where Tourism Brings Pricey Health Care, Locals Fight Back (KHN)

Julie Appleby, Kaiser Health News Colorado’s ski resort areas in Summit County have a high cost of living, among the highest in the country. The people who visit these places — Keystone, Breckenridge and Copper Mountain — can afford it. Many of those who live and work there can’t, especially when they get sick. In addition to expensive rent, they pay some of the steepest health insurance premiums in the nation. Hospital costs are also pricey, with most business generated by tourists, skiers and outdoors enthusiasts. But locals may soon get a break after a group, fed up with the costs, negotiated a deal with the hospital system. The group, which came to be known as the Peak Health Alliance, expects to be able to offer its members premiums next year that are at least 20% less than current rates. About 6,000 people, among them individuals as well as employees of local businesses and the county government, can buy coverage through the alliance, which cut a deal for a discount of about one-third off the local hospital’s list prices (although at least one expert thinks they could have done a lot better). “It wasn’t for the faint of heart,” said Tamara Drangstveit, who ran a county social services organization before becoming Peak’s executive director and, effectively, one of the lead negotiators. Fed up with high hospital prices even after insurers’ negotiated discount, more employers are cutting out insurance middlemen and engaging in what is known as “direct contracting” with medical providers. They cut their own deals. Direct contracting is a hot topic among employers because they are “up in arms about insurers not keeping prices in check,” said Chapin White, a Rand Corp. researcher who studies the tremendous variation in hospital prices. The citizens here in Colorado are taking the approach to the grassroots level. What Peak did — starting with painstakingly gathering data about exactly what hospitals in the region were being paid by insurers, employers and consumers — might be an answer for some. Such efforts may be helped by Congress, which is considering barring secrecy clauses in hospital and insurance contracts that can prevent employers from learning exactly how much insurers pay. The Trump administration is also considering proposals to require more public disclosure of negotiated hospital prices. And, according to press reports, the experience with Peak may go statewide. Colorado’s insurance commissioner and Gov. Jared Polis say they are considering an alliance that could bring together state employees, individuals and private employers in a similar health care purchasing network. “It feels like the curtain is going up on health care costs and prices,” said Cheryl DeMars, CEO of The Alliance, a group of 240 self-insured private sector employers that directly contracts with hospitals in Wisconsin, northern Illinois and eastern Iowa. While interest is growing, experts caution that direct contracting won’t work in many places. “It won’t have impact in urban areas where no one has significant market share, but it could work in rural areas where there is a dominant employer or some other large group,” said Gerard Anderson, a professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who researches health care costs. First Step: Get Price Information It takes a great deal of effort — and some luck — to peer behind the curtain. “The people buying the plans, employers and workers, are often barred from viewing the contracts insurers have negotiated on their behalf … so they don’t know if they are reasonable,” said White at Rand. The Peak Health Alliance in Colorado was lucky that the state is one of at least 18 that have made public some medical care price information from insurers. It also gathered similar information from local self-insured employers’ insurance plans. Peak was able to compare the payments made to Centura Health, which owns the local hospital and others in the state, to what Medicare would pay. “We found the average emergency room claim was 842% of what Medicare would pay — and our outpatient rates were 505% higher than Medicare,” Drangstveit said. That helps drive up premium costs. It isn’t unusual, Drangstveit said, for families who don’t qualify for a federal subsidy through the Affordable Care Act to face $2,500 monthly premiums with an $8,000 annual deductible. Many area residents go uninsured or are forced to make hard financial choices. “The stories we hear are heartbreaking,” said Drangstveit. Second Step: Negotiate With The Hospital Lee Boyles, CEO of Centura Health’s St. Anthony Summit Medical Center in Frisco, said he wasn’t surprised by the findings of Peak’s analysis. Charges are high, he said, reflecting the cost of living, as well as the need to maintain round-the-clock trauma coverage, emergency helicopter service and physicians who specialize in the kind of head and limb injuries that can result from mountain sports. Plus it’s the only hospital in town. Others are a 70-mile drive down the mountain in Denver. Unlike some hospitals elsewhere with similar exclusivity, Centura was willing to bargain. “We were going to do what’s right for our community,” said Boyles. It also helped that granting discounts to locals wouldn’t affect the bottom line much. Residents account for only about 15% of the hospital’s business, Boyles said, which is a far smaller portion than at a typical hospital. Tourists and sports enthusiasts — many well-heeled, with good insurance — make up the largest share of the hospital’s business. Thus, any new prices negotiated with Peak would not apply to most of the hospital’s business. The deal reached with Peak, Boyles said, represents a discount of about one-third off the hospital’s “list prices.” Third Step: Keep Pushing Anderson at Johns Hopkins said shaving this amount from already high charges isn’t much of a break. A discount pegged to Medicare rates, plus a bit for overhead and profit, would be better, he said. In a report released in May, Rand used claims data from employers in 25 states to show a huge variation in prices paid to specific hospitals and show a

Should I Accept a Winter Assignment Early?

By Alex McCoy, Contributing Writer, Owner of Fit Travel Life I know this seems like a weird topic to hit on in August, but I have been seeing posts pop up everywhere about how winter rates have arrived. While most hospitals do not start looking for travelers until three to four weeks out from their start date, a few hospital systems anticipate that cold and flu season will bring a need for extra staff and start hiring early. There are some definite pros to locking in a winter job ASAP, but also several drawbacks. So before you make a choice on whether or not to jump on those December and January start dates right now, be sure to consider all sides of the equation. Positives to Accepting a Winter Assignment Early 1. You alleviate the stress of looking for your next assignment If you are simply looking for job security or get burnt out waiting until the last second to apply for jobs, this could take some of that stress off your shoulders. At this point your fall contract is probably already secured, so by booking a winter assignment now you are locked into jobs for the next six months–which can be a relief. 2. Avoid the post-holiday rush so you can get the coveted January start date. My husband and I never worked a single holiday as travelers. We preferred to skip the holiday pay and head home around mid-December for a couple of weeks. However, the job market is flooded in December with people looking for early to mid-January start dates. Jobs can get pretty competitive or you may have to push a start back until February, so it may be nice to get a guarantee that you can get that holiday time off without having to fight for the perfect start date. 3. Plan ahead for finances and housing. If you are trying to go somewhere warm for the winter, housing prices may skyrocket a bit in that area because, well, so is everyone else. By having your contract in hand early, you are more likely to score some budget-friendly housing which can also allow you to make plans for financial goals heading into the new year. 4. Rates could drop depending on census. Right now hospitals are putting out mid to high pay packages to entice people to sign early. However, as the winter progresses rates may drop if the hospitals don’t get as busy as they are predicting. If you lock in the “winter rate” now, you will be guaranteed that rate unless you are canceled. Cons of Accepting a Winter Contract Early 1. Your life could change and the location may not be as desirable in 3 or 4 months. While we are always pretty flexible with location options, sometimes life has a way of dictating where we need to be and when. For example, if you have a string of weddings to attend back home or a family member is ill, or a new medical need pops up you may have to be more choosy about how close to home you stay. Locking in a location now prevents you from having a lot of flexibility if life shifts down the road. 2. Hospitals may overhire which could lead to higher rates of cancellation. The hospitals interested in getting travelers on board now are preemptively striking. This means they don’t actually know what their census will be in the winter, they are just guessing they will need the extra staff. If the patient population is lower than they anticipated this could lead to traveler layoffs which are never fun for us. 3. Overhiring could also lead to more floating for travelers. Most travelers realized floating is part of the job. However, floating every single shift or multiple times per shift can get old pretty fast. Before canceling a contract, hospitals will likely utilize travelers as float staff, which can be exhausting if that wasn’t what you anticipated from the beginning. 4. Winter rates could go up. On the other side of that coin, patient census could end up being much higher than anticipated which will force hospitals to raise rates to attract more travel nurses. In that case, everyone who signed early will be locked into the original pay rate, and newly signed travel nurses will be making more money for the same position. It doesn’t seem quite fair, but taking the gamble to wait could pay off if this is the case. While those winter rates are looking tempting, and having a contract planned way in advance may sound nice, I would highly recommend waiting until a little closer to the start date to actually think about accepting a contract. Between your personal life and changes within hospital systems, there is a lot that could change between now and December. My advice to all travelers right now is this: be patient. Winter rates are not going anywhere, and from experience, I would anticipate they will go up in the next several months before they drop. More hospitals will start hiring for winter needs, and your options will expand along with pay packages just like they do every other winter season. Alex McCoy currently works as a pediatric travel nurse. She has a passion for health and fitness, which led her to start Fit Travel Life in 2016. She travels with her husband, their cat, Autumn and their dog, Summer. She enjoys hiking, lifting weights, and trying the best local coffee and wine. << What I Would Change if I Could Reset My Travel Nursing Career

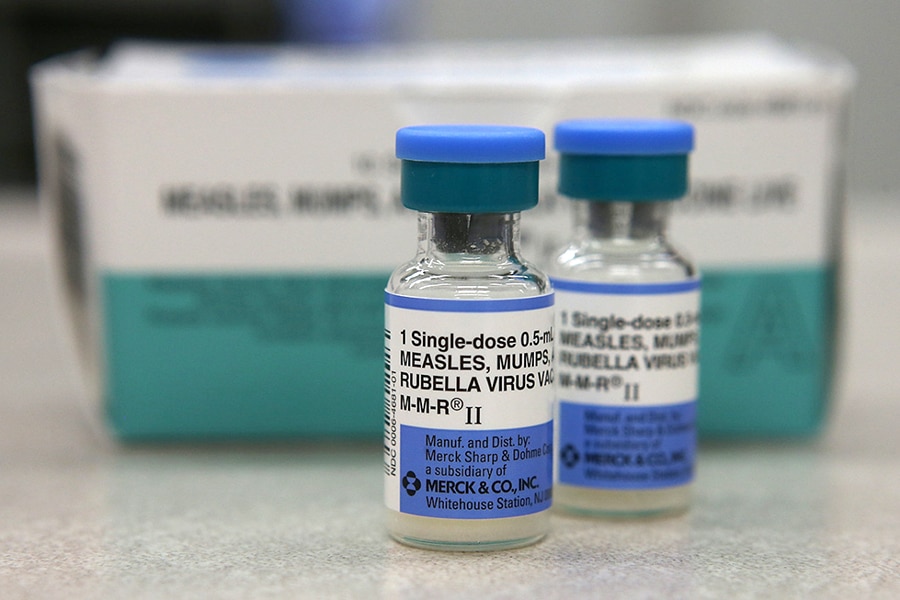

The Real-Life Conversion of a Former Anti-Vaxxer (KHN)

John M. Glionna, Kaiser Health News Amid the contentious dispute over immunization requirements for children, Kelley Watson Snyder stands out: She has been both a recalcitrant skeptic and an ardent proponent of childhood vaccines. Snyder, a Monterey, Calif., mother of two, was a so-called anti-vaxxer for many years, adding her voice to those that rejected mandatory vaccinations for school-age children. She later realized she was wrong and in 2014 founded a pro-vaccination Facebook group called “Crunchy Front Range Pro-Vaxxers,” which she administers. It is an invitation-only site on which approximately 1,100 members exchange views and information. Snyder, 38, is also an advocate for pending California legislation, SB 276, which targets bogus medical exemptions that allow unvaccinated children to attend school. The number of medical exemptions issued by physicians has risen sharply in recent years. The Medical Board of California is investigating at least four doctors for issuing questionable exemptions for children. Meanwhile, some infectious diseases once thought under control are breaking out again because parents failed to have their children vaccinated. Between Jan. 1 and July 25, 1,164 new measles cases were reported across 30 states, the most since the disease was declared eliminated in 2000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. California has seen 62 new measles cases this year. Kaiser Health News talked to Snyder about her transformation. Monterey, Calif., mother Kelley Watson Snyder, 38, poses with her two children, Jaylen, 9, and Kira, 5. Over time, she changed her opinion on vaccinations for her children, converting from an anti-vaxxer to an ardent proponent of vaccines who runs a pro-vaccination Facebook page. As a former opponent of mandatory childhood vaccines, can you describe the mindset? Anti-vaxxers have been around for a long time, but social media makes it easier to get into a loop. And once you’re there, it’s hard to see outside of it. Algorithms just show you more of what you’re already looking for. If you start searching anti-vaccination stories, that’s what starts popping up on your tagline. You start to think, “Oh, my God, there’s all these people and there’s so much of this going on.” But if you have a chance to peel back from that, you see that it’s actually a very small portion of the population who are really, really loud. The fear makes you angry and it makes you lash out. Once you get into that state, it’s easy to stay there. Describe a moment when you were in that state of mind. When my daughter was born, I refused the Vitamin K shot. I remember lying there with my daughter in my arms, and the nurses said, “Hey, we’re going to give her the vitamin K,” and I said, “No, we’re not doing that.” They made me sign a form that said I was going against the recommended medical care. At the time, the anti-vaxxer voices in my head said they were trying to coerce me into doing something dangerous for my child. They told me I was going to have to stay in the hospital longer for observation. I saw that as trying to force me to inject my child with this poison. What activities did you engage in as an anti-vaxxer? I joined some social media groups and would get together with some of those mothers who believed what I did. We used to call the pro-vaccination mothers “sheeple.” You’d ask them, “Have you thought about your stance? Have you even done any research?” Because when you’re in that anti-vax mindset, you spend all these hours on the internet, reading studies. I’ve come to realize that a Google search isn’t really research. Most times, you’re not reading an entire study, but only the abstract. What changed your mind on vaccinations? In the summer of 2014, I was in one particular anti-vaxxer Facebook group, and there was a debate going on about vaccines, and I started to notice that every time someone disagreed with them, the core members got belligerent, going straight to personal attacks. I also noticed that every single point they brought up had this immense conspiracy to go along with it. By that point, I’d started to think, “Do I really believe in all these conspiracies? Am I really that afraid, or can I go back and look at the evidence again?” By then, my daughter was 8 months old, and I just got over the fear I had as a first-time mom. I realized that my daughter was going to be OK. How do you think the vaccination fight will play out in California and nationally? I think California is setting a precedent for vaccine laws across the country. We’re making sure that medical exemptions for vaccines are not being bought, and that’s a very serious problem. Other states have seen the work we’ve done and they’re working on their own legislation. We’ve come to realize that unless we get more vocal about our pro-vaccine stance, the anti-vaccine voices just get louder and louder. I sometimes refer to anti-vaxxers as the drunk drivers of public health. They’re dangerous. What do you say today to the anti-vaxxers you once aligned with? I tell people that I understand their fears. I understand that parenting is very difficult, and all of us truly want the best for our children. I also know that the evidence is out there when people are willing to let their guards down. And I’m always happy to share real solid scientific evidence with people who want to do their critical thinking for themselves. I’m hoping people come around. I did. But we can’t force anybody. We just want to protect everyone else. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Differences Between Being a Pediatric Staff Nurse vs a Pediatric Travel Nurse

By Alex McCoy, Contributing Writer, Owner of Fit Travel Life In the course of my five years working as a nurse, all but thirteen weeks have been spent in pediatrics. Pediatric nursing is not for everyone, but I cannot imagine working with any other patient population. While there are some differences in travel versus perm positions that may apply to all specialties, I am going to focus on my favorite specialty this week. I have been fortunate enough to work in a variety of hospitals and units–from a 7-bed pediatric unit in a rural hospital to a children’s hospital system that boasts multiple campuses and level one trauma designation. All of these experiences have helped me learn more about the ins and outs of being a pediatric nurse, and the pros and cons of each setting. Here are my takeaways about working in pediatrics both as a staff nurse and a traveler. 1. Staff nurses have more opportunity to specialize Within pediatrics, there are a variety of specialties, similar to adult nursing. I have worked on hematology and oncology floors, liver and kidney transplant units, and floors that are a sort of “catch-all” of different specialties. Some hospitals are more restrictive about which types of patients travelers can take. For example, one facility did not allow travelers to administer chemotherapy. Another would not allow travelers to take fresh spinal fusions. Even if you are eager to learn the unit may not have time to adequately train you into a new area or may have policies restricting you from taking the higher acuity patients. While this can feel limiting, try not to take it to heart and remember you are still there to take the best care of your patients no matter the diagnosis or complexity. 2. Pediatric travelers may find inconsistency between policies One of the unique aspects of pediatrics is how precise some of our practices can be. Medication dosages and blood transfusion volumes are just two things that come to mind. Because we are so precise, there may be a variety of policies governing safety checks related to medications or other procedures. Even more confusing is that a lot of these policies will vary from facility to facility. The best practice I have found is to be respectful of the policies and procedures your particular facility uses. Unless you are concerned about the safety of the patient, it is best to comply with the rules of that particular organization. In the event that no policy exists, I use my best nursing judgment. This is a great example of why a solid background in your specialty is a necessity before you hit the road as a traveler. 3. Pediatric travelers may have to care for adult patients in some form or another While you should not expect to be the primary nurse for adult patients unless that was specified ahead of time, pediatric travelers may be asked to float to adult units to act as extra hands or as 1- on-1 sitter. If I know I interviewing for a pediatric job within an adult hospital, I make sure to ask if this will be a possibility in my interview. Each nurse may have a different level of comfort with this job requirement, so it is better to know the expectations ahead of time. 4. Full-time pediatric staff may have more opportunities to cross-train Before I started traveling I worked on a general pediatric unit. As I became more experienced I was offered opportunities to cross-train to both NICU and PICU. Eventually, they also offered to cross-train to postpartum and nursery. I enjoyed these opportunities to explore other specialties, especially in case I ever decided to switch my primary job. As a traveler, I have found most places are less likely to offer these opportunities. For one, if you are hired as a traveler, chances are the unit you are working on will be needing you the majority of the time. For another, most hospitals do not want to spare extra orientation days to an already short contract. Even if you are eager to help, these limitations may decrease your chances of working in areas outside of your specific hired unit. 5. While some of these differences are subtle, they are good things to consider when looking for a travel assignment I can’t say specifically whether these points are more pros or cons of staff versus travel jobs as a pediatric nurse. Each individual will have different opinions on what their preferred work setting or opportunities will be. Personally, I see all of the above as another set of considerations to weigh when deciding if travel nursing is the right career path for you. In addition, these points will help you decide if a specific job is the right fit. While pediatrics isn’t the highest paying or most talked-about travel specialty, it is still important for us peds travelers to know the caveats that come along with our unique specialty. Alex McCoy currently works as a pediatric travel nurse. She has a passion for health and fitness, which led her to start Fit Travel Life in 2016. She travels with her husband, their cat, Autumn and their dog, Summer. She enjoys hiking, lifting weights, and trying the best local coffee and wine. << What I Would Change if I Could Reset My Travel Nursing Career