Analysis: Can States Fix The Disaster Of American Healthcare? (KHN)

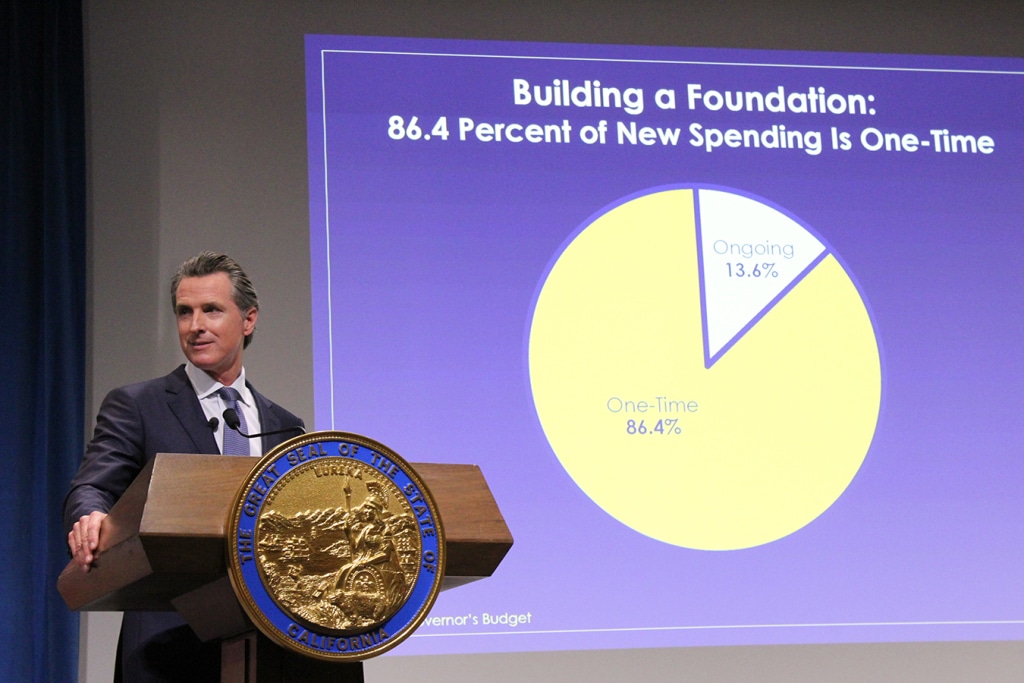

By Elisabeth Rosenthal, Kaiser Health News Last week, California’s new governor, Gavin Newsom, promised to pursue a smörgåsbord of changes to his state’s healthcare system: state negotiation of drug prices, a requirement that every Californian have health insurance, more assistance to help middle-class Californians afford it and healthcare for undocumented immigrants up to age 26. The proposals fell short of the sweeping government-run single-payer plan Newsom had supported during his campaign — a system in which the state government would pay all the bills and effectively control the rates paid for services. (Many California politicians before him had flirted with such an idea, before backing off when it was estimated that it could cost $400 billion a year.) But in firing off this opening salvo, Newsom has challenged the notion that states can’t meaningfully tackle healthcare on their own. And he’s not alone. A day later, Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington proposed that his state offer a public plan, with rates tied to those of Medicare, to compete with private offerings. New Mexico is considering a plan that would allow any resident to buy in to the state’s Medicaid program. And this month, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York announced a plan to expand healthcare access to uninsured, low-income residents of the city, including undocumented immigrants. For over a decade, we’ve been waiting for Washington to solve our healthcare woes, with endless political wrangling and mixed results. Around 70 percent of Americans have said that healthcare is “in a state of crisis” or has “major problems.” Now, with Washington in total dysfunction, state and local politicians are taking up the baton. The legalization of gay marriage began in a few states and quickly became national policy. Marijuana legalization seems to be headed in the same direction. Could reforming healthcare follow the same trajectory? States have always cared about healthcare costs, but mostly insofar as they related to Medicaid, since that comes from state budgets. “The interesting new frontier is how states can use state power to change the healthcare system,” said Joshua Sharfstein, a vice dean at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a former secretary of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. He added that the new proposals “open the conversation about using the power of the state to leverage lower prices in healthcare generally.” Already states have proved to be a good crucible for experimentation. Massachusetts introduced “Romneycare,” a system credited as the model for the Affordable Care Act, in 2006. It now has the lowest uninsured rate in the nation, under 4 percent. Maryland has successfully regulated hospital prices based on an “all payer” system. It remains to be seen how far the West Coast governors can take their proposals. Businesses — pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, doctors’ groups — are likely to fight every step of the way to protect their financial interests. These are powerful constituents, with lobbyists and cash to throw around. The California Hospital Association came out in full support of Newsom’s proposals to expand insurance (after all, this would be good for hospitals’ bottom lines). It offered a slightly less enthusiastic endorsement for the drug negotiation program (which is less certain to help their budgets), calling it a “welcome” development. It’s notable that his proposals didn’t directly take on hospital pricing, even though many of the state’s medical centers are notoriously expensive. Giving the state power to negotiate drug prices for the more than 13 million patients either covered by Medicaid or employed by the state is likely to yield better prices for some. But pharma is an agile adversary and may well respond by charging those with private insurance more. The governor’s plan will eventually allow some employers to join in the negotiating bloc. But how that might happen remains unclear. The proposal by Washington Gov. Inslee to tie payment under the public option plans to Medicare’s rates drew “deep concern” from the Washington State Medical Association, which called those rates “artificially low, arbitrary and subject to the political whims of Washington, D.C.” On the bright side, if Newsom or Inslee succeeds in making healthcare more affordable and accessible for all with a new model, it will probably be replicated one by one in other states. That’s why I’m hopeful. In 2004, the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. conducted an exhaustive nationwide poll to select the greatest Canadian of all time. The top-10 list included Wayne Gretzky, Alexander Graham Bell and Pierre Trudeau. No. 1 is someone most Americans have never heard of: Tommy Douglas. Douglas, a Baptist minister and left-wing politician, was premier of Saskatchewan from 1944 to 1961. Considered the father of Canada’s health system, he arduously built up the components of universal healthcare in that province, even in the face of an infamous 23-day doctors’ strike. In 1962, the province implemented a single-payer program of universal, publicly funded health insurance. Within a decade, all of Canada had adopted it. The United States will presumably, sooner or later, find a model for healthcare that suits its values and its needs. But 2019 may be a time to look to the states for ideas rather than to the nation’s capital. Whichever state official pioneers such a system will certainly be regarded as a great American. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, and also ran in the New York Times. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Need Health Insurance? The Deadline Is Dec. 15 (KHN)

By Michelle Andrews The woman arrived at the University of South Florida’s navigator office in Tampa a few weeks ago with a 40-page document describing a short-term health insurance plan she was considering. She was uncomfortable with what the broker had said about the coverage, she told Jodi Ray, a health insurance navigator who helps people enroll in coverage, and she wanted help understanding it. The document was confusing, according to Ray, who oversees Covering Florida, the state’s navigator program. It was hard to decipher which services would be covered. “It was like a bunch of puzzle pieces,” she said. Encouraged by her wife, the woman eventually opted instead for a marketplace plan with comprehensive benefits. The annual open-enrollment period for people who buy their own insurance on the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces ends Dec. 15 in most states. Enrollment in states that use the federal healthcare.gov platform has been sluggish this year compared to last. From Nov. 1 through Dec. 1, about 3.2 million people had chosen plans for 2019. Compared with the previous year, that’s about 400,000 fewer, or a drop of just over 11 percent. The wider availability of short-term plans is one big change that has set this year’s apart from past sign-up periods. Another is the elimination of the penalty for not having health insurance starting next year. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that as many as 3 million people who buy their own coverage may give it up when they don’t face a tax penalty. But experts who have studied health insurance enrollment say that surveys so far indicate that the penalty hasn’t typically been the pivotal factor in people’s decision on whether to buy insurance. They also caution against reading too much into the preliminary enrollment totals. “There typically is a surge in enrollment at the end,” said Sabrina Corlette, research professor at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. “It’s hard to know whether it will make up for the shortfall.” If they don’t pick a new plan, people who are enrolled in a 2018 marketplace plan may be automatically re-enrolled in their current plan or another one that is similar when the open-enrollment period ends. About a quarter of people who have marketplace plans are reassigned in this way. Another factor that may be affecting enrollment is tighter federal funding for the health insurance navigators, like Jodi Ray in Tampa, who guide consumers through the complicated process. With fewer experts available to answer questions and help fill out the enrollment forms, consumers may fall through the cracks. Across the country, funding for navigators dropped from $36 million in 2017 to $10 million this year. In Florida, federal funding for the Covering Florida navigator program was slashed to $1.25 million this year from $4.9 million last year, Ray said. The program was the only one to receive federal funding in the state this year. The Covering Florida program reduced the number of open-enrollment navigators to 59 this year, a nearly 61 percent drop, Ray said. Navigators this year are available in only half of Florida counties; the organization is offering telephone assistance and virtual visits to people in counties where they can’t offer in-person help. “It’s all we can do,” Ray said. So far, the group’s navigators have enrolled about half the number of people this year as they had last year. It’s unclear the extent to which the Trump administration’s efforts to reduce health care costs by expanding access to short-term plans is affecting marketplace plan enrollment. These plans, originally designed to cover people who expected to be out of an insurance plan for a short time, such as when they change jobs, can be less expensive. Unlike marketplace plans, short-term plans don’t have to provide comprehensive benefits or guarantee coverage for people who have preexisting medical conditions. The Obama administration limited short-term plans to a three-month term. But in August, the federal government issued a rule that allowed their sale with initial terms of up to a year, and the option of renewal for up to three years. Ten states either ban short-term plans or restrict them to terms of less than three months, said Sarah Lueck, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Many people are seemingly not focused on their options this open-enrollment season, however. According to a recent survey, about half of adults under age 65 who were uninsured or who buy their own coverage said they planned to buy a plan for 2019. But only 24 percent of people in that age group said they knew what the deadline was to enroll in health insurance, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s November health tracking poll. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Election’s Impact On Healthcare: Some Bellwether Races To Watch

By Julie Rovner, Kaiser Health News Voters this year have told pollsters in no uncertain terms that health care is important to them. In particular, maintaining insurance protections for preexisting conditions is the top issue to many. But the results of the midterm elections are likely to have a major impact on a broad array of other health issues that touch every single American. And how those issues are addressed will depend in large part on which party controls the U.S. House and Senate, governors’ mansions and state legislatures around the country. All politics is local, and no single race is likely to determine national or even state action. But some key contests can provide something of a barometer of what’s likely to happen — or not happen — over the next two years. For example, keep an eye on Kansas. The razor-tight race for governor could determine whether the state expands Medicaid to all people with low incomes, as allowed under the Affordable Care Act. The legislature in that deep red state passed a bill to accept expansion in 2017, but it could not override the veto of then-Gov. Sam Brownback. Of the candidates running for governor in 2018, Democrat Laura Kelly supports expansion, while Republican Kris Kobach does not. Here are three big health issues that could be dramatically affected by Tuesday’s vote. 1. The Affordable Care Act Protections for preexisting conditions are only a small part of the ACA. The law also made big changes to Medicare and Medicaid, employer-provided health plans and the generic drug approval process, among other things. Republicans ran hard on promises to get rid of the law in every election since it passed in 2010. But when the GOP finally got control of the House, the Senate and the White House in 2017, Republicans found they could not reach agreement on how to “repeal and replace” the law. This year has Democrats on the attack over the votes Republicans took on various proposals to remake the health law. Probably the most endangered Democrat in the Senate, Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, has hammered her Republican opponent, U.S. Rep. Kevin Cramer, over his votes in the House for the unsuccessful repeal-and-replace bills. Cramer said that despite his votes he supports protections for preexisting conditions, but he has not said what he would do or get behind that could have that effect. Polls suggest Cramer has a healthy lead in that race, but if Heitkamp pulled off a surprise win, health care might well get some of the credit. And in New Jersey, Rep. Tom MacArthur, the moderate Republican who wrote the language that got the GOP health bill passed in the House in 2017, is in a heated race with Democrat Andy Kim, who has never held elective office. The overriding issue in that race, too, is health care. It is not just congressional action that has Republicans playing defense on the ACA. In February, 18 GOP attorneys general and two GOP governors filed a lawsuit seeking a judgment that the law is now unconstitutional because Congress in the 2017 tax bill repealed the penalty for not having insurance. Two of those attorneys general — Missouri’s Josh Hawley and West Virginia’s Patrick Morrisey — are running for the Senate. Both states overwhelmingly supported President Donald Trump in 2016. The attorneys general are running against Democratic incumbents — Claire McCaskill of Missouri and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. And both Republicans are being hotly criticized by their opponents for their participation in the lawsuit. Although Manchin appears to have taken a lead, the Hawley-McCaskill race is rated a toss-up by political analysts. But in the end, the fate of the ACA depends less on an individual race than on which party winds up in control of Congress. “If Democrats take the House … then any attempt at repeal-and-replace will be kaput,” said John McDonough, a former Democratic Senate aide who helped write the ACA and now teaches at the Harvard School of Public Health. Conservative healthcare strategist Chris Jacobs, who worked for Republicans on Capitol Hill, said a new repeal-and-replace effort might not happen even if Republicans are successful Tuesday. “Republicans, if they maintain the majority in the House, will have a margin of a half dozen seats — if they are lucky,” he said. That likely would not allow the party to push through another controversial effort to change the law. Currently, there are 42 more Republicans than Democrats in the House. Even so, the GOP barely got its health bill passed out of the House in 2017. And political strategists say that, when the dust clears after voting, the numbers in the Senate may not be much different so a change could be hard there too. Republicans, even with a small majority last year, could not pass a repeal bill there. 2. Medicaid expansion The Supreme Court in 2012 made optional the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to cover all low-income Americans up to 138 percent of the poverty line ($16,753 for an individual in 2018). Most states have now expanded, particularly since the federal government is paying the vast majority of the cost: 94 percent in 2018, gradually dropping to 90 percent in 2020. Still, 17 states, all with GOP governors or state legislatures (or both), have yet to expand Medicaid. McDonough is confident that’s about to change. “I’m wondering if we’re on the cusp of a Medicaid wave,” he said. Four states — Nebraska, Idaho, Utah and Montana — have Medicaid expansion questions on their ballots. All but Montana have yet to expand the program. Montana’s question would eliminate the 2019 sunset date included in its expansion in 2016. But it will be interesting to watch results because the measure has run into big-pocketed opposition: the tobacco industry. The initiative would increase taxes on cigarettes and other tobacco products to fund the state’s increased Medicaid costs. In Idaho, the ballot measure is being embraced by a number of Republican leaders. GOP Gov.

Listen: A Sudden Freeze On ACA Payouts And What It Means For You

Over the weekend, Seema Verma, administrator for the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said she was suspending $10 billion in “risk adjustment” payments that helped stabilize the insurance markets created under the health law. Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent and host of KHN’s What The Health podcast, explains the national picture on the Takeaway for WNYC: Can’t see the audio player? Click here to download. Chad Terhune, senior correspondent, explains the effects of this development in California and other states for South California Public Radio: Can’t see the audio player? Click here to download. They examine what health insurers and Covered California officials have described as another curveball from the Trump administration meant to weaken the Affordable Care Act. Verma said the “risk-adjustment” payments and collections had to be halted in response to a New Mexico court ruling in February that said elements of the program were flawed. Another court in Massachusetts had upheld the program in January. The risk-adjustment program was meant to stabilize the insurance exchanges by taking money made through low-risk consumers and shifting it to higher-risk pools. The federal government collects money from some insurers that enrolled healthier patients and then transfers money to other insurers who had sicker enrollees. Because the Affordable Care Act requires insurers to accept all people regardless of their medical history or preexisting conditions, architects of the law created the program to prevent insurance companies from cherry-picking the healthiest people. The Republican-led Congress failed last year to repeal and replace the ACA. However, Republican lawmakers and the Trump administration have made a series of moves intended to weaken the health law, such as halting subsidies that covered some consumers’ out-of-pocket costs and eliminating the penalty. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News (KHN) Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Medicare Financial Outlook Worsens

Phil Galewitz, Kaiser Health News Medicare’s financial condition has taken a turn for the worse because of predicted higher hospital spending and lower tax revenues that fund the program, the federal government reported Tuesday. In its annual report to Congress, the Medicare board of trustees said the program’s hospital insurance trust fund could run out of money by 2026 — three years earlier than projected last year. A senior government official briefing reporters attributed the worsened outlook for Medicare to several factors that are reducing funding and increasing spending. He said the trustees projected lower wages for several years, which will mean lower payroll taxes, which help fund the program. The recent tax cut passed by Congress would also result in fewer Social Security taxes paid into the hospital trust fund, as some higher-income seniors pay taxes on their Social Security benefits. The aging population is also putting pressure on the program’s finances. In addition, he said moves by the Trump administration and the GOP-controlled Congress to kill two provisions of the Affordable Care Act are also harming Medicare’s future. Those were the repeal of the penalties for people who don’t have insurance and the repeal of an independent board charged with reining in spending if certain financial targets were reached. Marc Goldwein, senior vice president for the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said it was not surprising to see the three-year shift in Medicare’s solvency since the trust fund operates on a narrow margin between revenue and expenses. He said the change to the ACA’s individual mandate penalties, which takes effect next year, is expected to lead to millions more people going without health insurance. That, in turn, will leave hospitals with higher rates of uncompensated care. Some of those expenses are covered by a special Medicare fund paid to hospitals with larger numbers of uninsured patients. The Medicare Part A hospital trust fund is financed mostly through payroll taxes. It helps pay hospital, home health services, nursing home and hospice costs. Medicare Part B premiums — which cover visits to physicians and other outpatient costs — should remain stable next year, the trustees said. About a quarter of Part B costs are paid for by beneficiary premiums with the rest from the federal budget. In a separate report, the government said that Social Security would be able to pay full benefits until 2034, the same estimate as last year. The Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund was projected to have sufficient funds until 2032, four years later than forecast last year. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin downplayed any pending crisis, although he acknowledged Medicare faces many long-standing economic and demographic challenges. “Lackluster economic growth in previous years, coupled with an aging population, has contributed to projected shortages for both Social Security and Medicare,” he said in a statement. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0404 Mnuchin vowed that the Trump administration’s efforts to cut taxes, ease federal regulations and improve trade deals would help both Medicare and Social Security survive over the long term. “Robust economic growth will help to ensure their lasting stability,” he said. Critics, however, doubt the economy will grow fast enough to fix Medicare. The top Democrat on the House Ways & Means Committee, Rep. Richard Neal (Mass.), blamed the Trump administration for Medicare’s deteriorating outlook. “Administration policies in President Trump’s first year have reduced the life of the Medicare trust fund by three years,” he said. “With their repeated efforts to sabotage the nation’s health care system, including their irresponsible tax law, congressional Republicans and President Trump are purposefully running Medicare into the ground.” Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said in a statement the report should spur Congress to act on Trump’s budget plan to cut Medicare spending during the next decade, mostly by reducing payments to doctors, nursing homes and other providers. “These proposals, if enacted, would strengthen the integrity of the Medicare program,” she said. Breaking from tradition, none of the Medicare trustees — which include Mnuchin, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta — spoke to the press after releasing the report. A spokesman said they had “scheduling conflicts.” The Medicare trustees said the trust fund will be able to pay full benefits until 2026 but then it will gradually decline to be able to cover 78 percent of expenses in 2039. Medicare provides health coverage to more than 58 million people, including seniors and people with disabilities. It has added 7 million people since 2013. Total Medicare expenditures were $710 billion in 2017. Juliette Cubanksi, associate director of Kaiser Family Foundation’s Medicare Policy Program, cautioned that the report doesn’t mean Medicare is going bankrupt in the next decade but Part A will only be able to pay 91 percent of covered benefits starting in 2026. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.) She noted that Congress has never let the trust fund go bankrupt. In the early 1970s, the program came within two years of insolvency. But the 2026 estimate marks the closest the program has come to insolvency since 2009, the year before the Affordable Care Act was approved. Joe Baker, president of the Medicare Rights Center, said Congress still has plenty of time to act without making changes that harm beneficiaries. “I worry about fear mongering and the need to do something radical to the program,” he said. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.