New York Nurses Set April Strike Date At 3 Hospital Systems

Registered nurses at three New York healthcare systems issued a 10-day strike notice on Monday, amid claims of unsafe working conditions caused by inadequate staffing, according to a recent union press release. New York State Nurses Association members delivered the strike notice to New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Montefiore, and Mount Sinai hospitals and set the strike date for April 2. The strike could affect more than 10,000 nurses at the three hospitals, according to the union, which have been in contract negotiations for several months with the New York City Hospital Alliance. More than 8,000 members of the nurses union voted earlier this month to authorize a strike if necessary. Union contracts at the facilities ended on December 31, but both parties have met about 30 times at barganing sessions with limited progress, according to an ABC 7 NY report. “Now is the time that all New Yorkers must have what they need and deserve,” Robin Krinsky, RN, NYSNA Board Member and negotiating committee member at Mount Sinai, said in a NYSNA Facebook post. “Safe patient care by educated professional nurses who know how to provide excellent care each and every time a patient requires it.” The union claims nurses are working with anywhere from 9 to 10 patients at at once, and has protested in support of legislation that would establish mandated nurse-to-patient ratios. A “Safe Staffing For Quality Care Act” bill that would establish mandated ratios statewide was reintroduced during this year’s legislative session, and is currently in committee for review. Advocates have pushed for mandated ratios since 2009, when a version of the bill was first introduced.

Death By 1,000 Clicks: Where Electronic Health Records Went Wrong (KHN)

By Fred Schulte, Kaiser Health News and Erika Fry, Fortune The pain radiated from the top of Annette Monachelli’s head, and it got worse when she changed positions. It didn’t feel like her usual migraine. The 47-year-old Vermont attorney turned innkeeper visited her local doctor at the Stowe Family Practice twice about the problem in late November 2012, but got little relief. Two months later, Monachelli was dead of a brain aneurysm, a condition that, despite the symptoms and the appointments, had never been tested for or diagnosed until she turned up in the emergency room days before her death. Monachelli’s husband sued Stowe, the federally qualified health center the physician worked for. Owen Foster, a newly hired assistant U.S. attorney with the District of Vermont, was assigned to defend the government. Though it looked to be a standard medical malpractice case, Foster was on the cusp of discovering something much bigger — what his boss, U.S. Attorney Christina Nolan, calls the “frontier of health care fraud” — and prosecuting a first-of-its-kind case that landed the largest-ever financial recovery in Vermont’s history. Foster began with Monachelli’s medical records, which offered a puzzle. Her doctor had considered the possibility of an aneurysm and, to rule it out, had ordered a head scan through the clinic’s software system, the government alleged in court filings. The test, in theory, would have caught the bleeding in Monachelli’s brain. But the order never made it to the lab; it had never been transmitted. The software in question was an electronic health records system, or EHR, made by eClinicalWorks (eCW), one of the leading sellers of record-keeping software for physicians in America, currently used by 850,000 health professionals in the U.S. It didn’t take long for Foster to assemble a dossier of troubling reports — Better Business Bureau complaints, issues flagged on an eCW user board, and legal cases filed around the country — suggesting the company’s technology didn’t work quite the way it said it did. Until this point, Foster, like most Americans, knew next to nothing about electronic medical records, but he was quickly amassing clues that eCW’s software had major problems — some of which put patients, like Annette Monachelli, at risk. Damning evidence came from a whistleblower claim filed in 2011 against the company. Brendan Delaney, a British cop turned EHR expert, was hired in 2010 by New York City to work on the eCW implementation at Rikers Island, a jail complex that then had more than 100,000 inmates. But soon after he was hired, Delaney noticed scores of troubling problems with the system, which became the basis for his lawsuit. The patient medication lists weren’t reliable; prescribed drugs would not show up, while discontinued drugs would appear as current, according to the complaint. The EHR would sometimes display one patient’s medication profile accompanied by the physician’s note for a different patient, making it easy to misdiagnose or prescribe a drug to the wrong individual. Prescriptions, some 30,000 of them in 2010, lacked proper start and stop dates, introducing the opportunity for under- or overmedication. The eCW system did not reliably track lab results, concluded Delaney, who tallied 1,884 tests for which they had never gotten outcomes. The District of Vermont launched an official federal investigation in 2015. The eCW spaghetti code was so buggy that when one glitch got fixed, another would develop, the government found. The user interface offered a few ways to order a lab test or diagnostic image, for example, but not all of them seemed to function. The software would detect and warn users of dangerous drug interactions, but unbeknownst to physicians, the alerts stopped if the drug order was customized. “It would be like if I was driving with the radio on and the windshield wipers going and when I hit the turn signal, the brakes suddenly didn’t work,” said Foster. The eCW system also failed to use the standard drug codes and, in some instances, lab and diagnosis codes as well, the government alleged. The case never got to a jury. In May 2017, eCW paid a $155 million settlement to the government over alleged “false claims” and kickbacks — one physician made tens of thousands of dollars — to clients who promoted its product. Despite the record settlement, the company denied wrongdoing; eCW did not respond to numerous requests for comment. If there is a kicker to this tale, it is this: The U.S. government bankrolled the adoption of this software — and continues to pay for it. Or we should say: You do. Which brings us to the strange, sad, and aggravating story that unfolds below. It is not about one lawsuit or a piece of sloppy technology. Rather, it’s about a trouble-prone industry that intersects, in the most personal way, with every one of our lives. It’s about a $3.7 trillion health care system idling at the crossroads of progress. And it’s about a slew of unintended consequences — the surprising casualties of a big idea whose time had seemingly come. The Virtual Magic Bullet Electronic health records were supposed to do a lot: make medicine safer, bring higher-quality care, empower patients, and yes, even save money. Boosters heralded an age when researchers could harness the big data within to reveal the most effective treatments for disease and sharply reduce medical errors. Patients, in turn, would have truly portable health records, being able to share their medical histories in a flash with doctors and hospitals anywhere in the country — essential when life-and-death decisions are being made in the ER. But 10 years after President Barack Obama signed a law to accelerate the digitization of medical records — with the federal government, so far, sinking $36 billion into the effort — America has little to show for its investment. KHN and Fortune spoke with more than 100 physicians, patients, IT experts and administrators, health policy leaders, attorneys, top government officials and representatives at more than a half-dozen EHR vendors, including

New York, Rhode Island Nursing Unions Vote To Authorize Strikes

Members of registered nurse unions in New York and Rhode Island have both voted to allow union representatives to issue 10-day strike notices if necessary, according to recent reports. United Nurses & Allied Professionals (UNAP) members in Rhode Island voted Wednesday to authorize a strike notice for Fatima Hospital, located in northern Providence. Workers want to bring attention to what they claim is a lack of commitment to patient and worker safety under Prospect CharterCARE, according to a WPRI report. Fatima Hospital is an affiliate of Prospect CharterCARE. “We don’t take this step lightly and we realize what’s at stake for each other, our patients and the community we are proudly a part of,” Cindy Fenchel, president of UNAP Local 5110 said to WPRI. “It’s time for Prospect CharterCARE to come to the table and make substantive commitments on improving patient care and strengthening worker safety.” In New York, more than 8,000 members of the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA) voted to authorize a 10-day strike notice amid ongoing contract negotiations with New York City Hospital Alliance, according to a recent blog post. The collective bargaining agreement between the two organizations ended on December 31. NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, Montefiore, Mt. Sinai, Mt. Sinai West, and St. Luke’s hospitals are involved in the negotiations, and a potential strike could affect an estimated 10,000 nurses at those facilities. Nurses held open protests against the 13 facilities in February over what they claim are unsafe working conditions and inadequate staffing levels. New York City Hospital Alliance disputes these claims and said NYSNA has not provided a “single shred of evidence” to support this claim, according to a CBS WLNY report. “We have remained committed to bargaining in good faith and have put forward a significant proposal that demonstrates the value we place on our nurses, who are the best in the business and should be rewarded for their essential role in the delivery of excellent care,” Farrell Sklerov, a spokesperson for the Hospital Alliance told WLNY.

‘These Women’s Lives Mattered’: Nurse Builds Database Of Women Murdered By Men (KHN)

By Natalie Schreyer, Kaiser Health News PLANO, Texas — In February 2017, a school nurse in this Dallas suburb began counting women murdered by men. Seated at her desk, beside shelves of cookbooks, novels and books on violence against women, Dawn Wilcox, 55, scours the internet for news stories of women killed by men in the U.S. For dozens of hours each week, she digs through online news reports and obituaries to tell the stories of women killed by lovers, strangers, fathers, sons and stepbrothers, neighbors and tenants. “I’m trying to get the message [across] that women matter, and that these women’s lives mattered, and that this is not acceptable in the greatest country in the world,” Wilcox said. Her spreadsheet, a publicly available resource she calls Women Count USA, is a catalog of lives lost: names, dates, ages, where they lived, pictures of victims and their alleged killers, and the details that can’t be captured by numbers. For Wilcox, these women are more than statistics. She wants you to know Nicole Duckson, a 34-year-old Columbus, Ohio, woman whose friends “remembered her as a prayerful person and a loving mother.” And Duckson’s 4-year-old daughter, Christina, who was stabbed to death alongside her mother, “a polite, happy little girl.” And Claire Elizabeth VanLandingham, 27, a Navy dentist fatally shot by her ex-boyfriend. She had appeared in a video for Take Back the Night, the organization known for fighting dating violence, sexual violence and domestic violence on college campuses nationally. Her mother said, “Her heart was kind; her spirit generous; her soul wise. She gave her smile to everyone who needed it; to everyone who hadn’t even realized they did.” Those are just a few of the nearly 2,500 women listed in Wilcox’s album during the past two years. “Where is the outrage? Where are the marches, the speeches? I know where the silence is. It is everywhere and it is deafening,” Wilcox said. Her crusade, Wilcox said, was spurred in part by the media frenzy about the shooting death of a gorilla, Harambe, at the Cincinnati Zoo and the uproar over the killing of Cecil the Lion, shot by a Minnesota dentist as a trophy. As an animal lover, she was horrified by those killings. But as she saw the social media fury and the online petitions spread, she asked herself: “But what about women?” “Women are people and they deserve to have their lives valued,” she posted on Facebook in 2016 after Harambe’s death. “They deserve our voices speaking out on their behalf. And when they are abused, assaulted, murdered and erased they deserve our attention and our outrage.” Tracking The Data The FBI releases crime data every year, including the number of women who have been killed by men, but local police are not required to file reports to the federal agency, so some state figures are missing. Florida, for example, has not provided its data to the FBI since 1996, according to reports by the Violence Policy Center, a nonprofit organization that advocates to stop gun violence. Numbers from Alabama and Illinois have also been unavailable or limited in certain years. Since 1996, between 1,613 and 2,129 women were murdered by men each year, FBI data show. In 2017, the latest year for which data are available, the FBI counted 1,733 women. An overwhelming majority of those women were killed by a man they knew. “If you just go by the raw numbers, it is undoubtedly an undercount of domestic violence homicides,” said April Zeoli, an associate professor of criminal justice at Michigan State University and an expert on domestic violence homicides and gun laws. Still, she added, “it’s the most accurate picture we have.” Wilcox, however, is doing something the FBI does not: putting faces to the cases. Recording the correct number of women murdered isn’t the only goal of Wilcox’s effort. Her work is about searching for their stories, finding their photos, trying to learn who they were, so that these women aren’t forgotten. Touched By Abuse Wilcox is no stranger to violence against women. When she was 21, she began dating a man she met in a bar in Dallas. She’ll never forget the first time he hurt her. On a night out at a dance club, Wilcox’s boyfriend stepped into the restroom. When he came back, she said, he sprayed cologne into her face, burning her eyes as she groped her way to the bathroom to rinse it out. It was an accident, she said he told her. But Wilcox knew it was an attempt to humiliate her. The violence escalated, Wilcox said, culminating in a night that left a deep scar on the inside of her arm and a memory of abuse that echoes the stories of the lost women for whom she searches. It was hot and the power had gone out, leaving her with no air conditioning as she read a book by candlelight in her apartment. The man began kissing her leg, she said, but soon she felt his teeth digging into her as he bit her. She told him to stop, but he put his hand to the base of her throat, pushed her down onto the bed and, after telling her he wanted to taste her blood, bit into the crook of her arm, tearing out skin, she said. Wilcox went to a hospital emergency room and then fled to her mother’s home. She eventually ended the relationship with the man. He was subsequently convicted of sexual assault and kidnapping after he raped two women before forcing them into his car, driving them to a secluded, wooded area, knocking them out and threatening to kill them. The women managed to escape. Wilcox considers herself lucky. “I could’ve easily ended up one of the women on my own list.” Today, she is married to a man who said his wife’s work has opened his eyes to the pervasiveness of violence against women. “She’s inspired me,” said Mike Nosenzo,

US Measles Cases Surpass 2016, 2017 Totals, CDC Reports

The number of measles cases in 2019 has already surpassed annual totals for 2016 and 2017, according to a recent Center for Disease Control and Prevention report. At least 127 cases have been recorded this year as of last Thursday, which is an increase of 48 more cases since February 4. The annual totals for 2016 and 2017 were 86 and 120, respectively. CDC officials linked the spread of measles cases to unvaccinated travelers who have brought the virus back from countries experiencing large measles outbreaks, like Ukraine and Israel. Individual measles cases have occurred in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, New York, Oregon, Texas and Washington. Five outbreaks, defined as three or more cases recorded in an area, have occurred in New York, Texas and Washington. Among all of the recorded cases, Washington has been hit the hardest by the spread of measles. Almost half of all measles cases—64 in total as of Thursday—have occurred in Washington state’s Clark County, according to a recent report by Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). Washington Gov. Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency in late January, directing state agencies and departments to divert as many resources as possible to assist affected areas. While 2019 has seen a sharp increase in measles cases, 2014 holds the record of the most cases in the past decade, according to CDC data. A total of 667 cases were recorded in 2014, more than half of which occurred in one outbreak among an unvaccinated Amish community in Ohio.

Shrinking Medicaid Rolls In Missouri And Tennessee Raise Flag On Vetting Process

By Phil Galewitz, Kaiser Health News Tangunikia Ward, a single mom of two who has been unemployed for the past couple of years, was shocked when her St. Louis family was kicked off Missouri’s Medicaid program without warning last fall. She found out only when taking her son, Mario, 10, to a doctor to be treated for ringworm. When Ward, 29, tried to contact the state to get reinstated, she said it took several weeks just to have her calls returned. Then she waited again for the state to mail her a long form to fill out attesting to her income and family size, showing that she was still eligible for the state-federal health insurance program for the poor. Mario, who is in third grade, missed much of school in December because Ward could not afford a doctor visit without Medicaid. His school would not let him return without a doctor’s note saying he was no longer infected. In January, with the help of lawyers from Legal Services of Eastern Missouri, she was able to get back on Medicaid, take her son to a doctor and return him to school. “It was a real struggle as it seemed like everyone was giving me the runaround,” Ward said. “I am upset because my son was out of school, and that pushed him behind.” Ward and her children are among tens of thousands of Medicaid enrollees who were dropped by Missouri and Tennessee last year as both states stepped up efforts to verify members’ eligibility. Last year, Medicaid enrollment there declined far faster than in other states, and most of those losing coverage are children, according to state data. State health officials say several factors, including the improved economy, are behind last year’s drop of 7 percent in Missouri and 9 percent in Tennessee. But advocates for the poor think the states’ efforts to weed out residents who are improperly enrolled, or the difficulty of re-enrolling, has led to people being forced off the rolls. For example, Tennessee sent packets to enrollees that could be as long as 47 pages to verify their re-enrollment. In Missouri, people faced hours-long waits on the state’s phone lines to get help in enrolling. Medicaid enrollment nationally was down about 1.5 percent from January to October last year, the latest enrollment data available from the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Herb Kuhn, president and chief executive of the Missouri Hospital Association, said the state’s efforts to verify Medicaid eligibility could be tied to an increase in the number of people without coverage that hospitals are seeing. “When we see over 50,000 children come off the Medicaid rolls, it raises some questions about whether the state is doing its verifications appropriately,” he said. “Those who are truly entitled to the service should get to keep it.” In 2018, Missouri Medicaid began automating its verification system for the state-federal insurance program for the poor. People who were identified as ineligible, for income or other reasons, were sent a letter asking them to provide updated documentation. Those who did not respond or could not prove their eligibility were dropped. The state does not know how many letters it sent or how many people responded, said Rebecca Woelfel, spokeswoman for the Missouri Department of Social Services, which oversees Medicaid. She said Missouri Medicaid enrollees were given 10 days to respond. Woelfel cited the new Medicaid eligibility system, the improved economy and Congress rescinding the federal tax penalty for people who lack insurance as factors behind the decline in enrollment. Missouri’s unemployment rate dropped from 3.7 percent in January 2018 to 3.1 percent in December as the number of unemployed people fell by about 17,000. Missouri Medicaid had almost 906,000 people enrolled as of December, down from more than 977,000 in January 2018, according to state data. About two-thirds of those enrolled are children or pregnant women. Timothy McBride, a health economist at Washington University in St. Louis who heads a Missouri Medicaid advisory board, said the state’s Medicaid eligibility system has made it too difficult for people to stay enrolled. Since low-income people move or may be homeless, their mailing addresses may be inaccurate. Plus, many don’t read their mail or may not understand what was required to stay enrolled, he added. “I worry some people are still eligible but just did not respond, and the next time they need health care they will show up with their Medicaid card and find out they are not covered,” McBride said. Tennessee’s Medicaid enrollment fell from 1.48 million in January 2018 to 1.35 million in December, according to state data. Tennessee Medicaid spokeswoman Kelly Gunderson credits a healthy job market. The state’s unemployment rate was relatively stable last year at under 4 percent. “Tennessee is experiencing a state economy that continues to increase at what appears to be near-historic rates, which is positively impacting Tennesseans’ lives and, in some cases, decreasing their need to access health insurance through the state’s Medicaid” program and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), she said. She added that the state has a “robust appeals process” for anyone who was found ineligible by the state’s reverification system. The Tennessee Justice Center, an advocacy group, has worked with hundreds of families in the past year trying to restore their Medicaid coverage. The verification process will make “Medicaid rolls smaller and saves money, and that’s a poor way for the state to measure success,” said Michele Johnson, executive director of the nonprofit group. “But it’s penny-wise and pound-foolish” because it leads to people showing up at emergency rooms without coverage — and hospitals have to pass on those costs to everyone else. After rapid growth since 2014, when the Affordable Care Act expanded health insurance coverage to millions of Americans, Medicaid enrollment nationally started to fall, declining from 74 million in January 2018 to about 73 million in October, according to the latest enrollment data released by CMS. Missouri and Tennessee are among 17

Baylor Scott & White, Memorial Hermann Health Mega Merger Called Off

Two major Texas hospital systems, Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas and Memorial Hermann Health System in Houston, called off a mega merger deal Tuesday that would have created the largest hospital system in the state. No specific reason was given for the cancellation. “After months of thoughtful exploration, we have decided to discontinue talks of a merger between our two systems. Ultimately, we have concluded that as strong, successful organizations, we are capable of achieving our visions for the future without merging at this time,” a hospital spokesperson said in a joint statement. “We have a tremendous amount of respect for each other and remain committed to strengthening our communities, advancing the health of Texans and transforming the delivery of care. We will continue to seek opportunities for collaboration as two forward-thinking, mission-driven organizations.” If the merger had passed, the system would have managed 68 hospitals and more than 73,000 employees. It also would have created one of the largest not-for-profit systems by revenue, according to Modern Healthcare. Baylor Scott & White Health and Memorial Hermann Health signed a letter of intent in October to merge “to further strengthen communities, advance the health of Texans and transform the delivery of healthcare.” Another huge year for hospital, healthcare mergers While this mega merger deal fell through, several other major joint ventures made headlines in 2018, capping off another year of increased mergers and acquisitions activity in the healthcare industry. The total volume of deals increased by 14.4 percent from 2017 to 2018, according to an analysis by PricewaterhouseCoopers, although the value of those deals declined more than 30 percent, and slowed some in Q4. Of all the healthcare deals in 2018, the largest and most notable was CVS Health’s acquisition of Aetna for $69 billion, which was finalized in November. “Today marks the start of a new day in healthcare and a transformative moment for our company and our industry,” CVS Health President and Chief Executive Officer Larry J. Merlo said in a press release. “By delivering the combined capabilities of our two leading organizations, we will transform the consumer health experience and build healthier communities through a new innovative health care model that is local, easier to use, less expensive and puts consumers at the center of their care.” Healthcare leaders are still waiting to see how this landmark deal will impact the industry and marketplace, and providers are wary that the merger could create a landscape that incentivizes use of urgent care centers and retail clinics over traditional healthcare facilities, according to a report from Revcycle Intelligence. Merger and acquisition activity in 2019 is expected to remain strong, although healthcare executives expect the actual volume of activity will level out, according to a recent survey by Capital One.

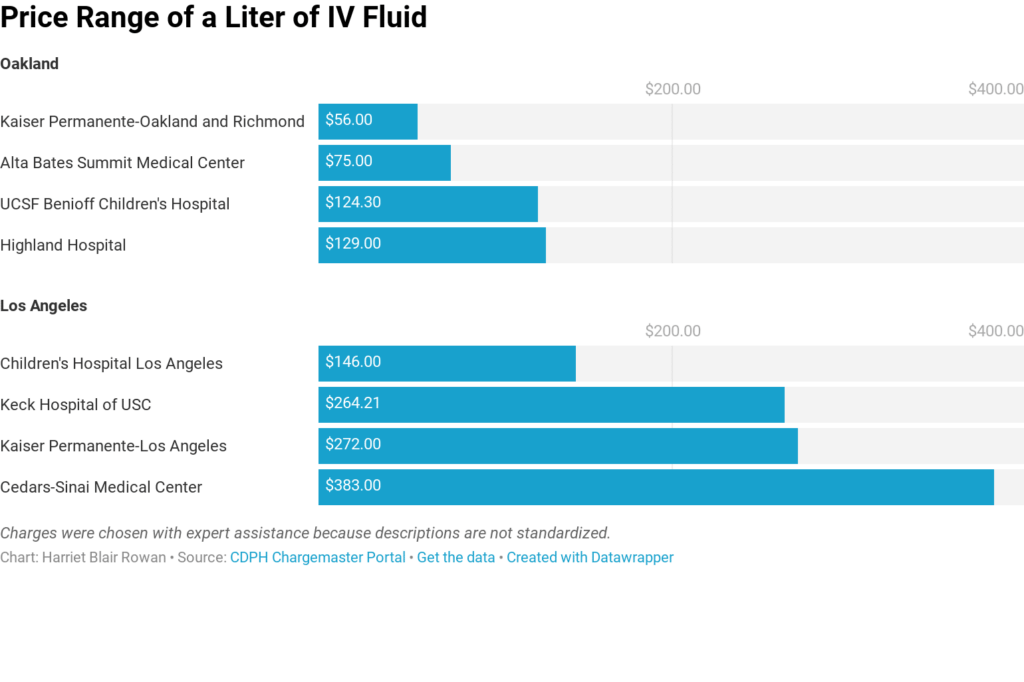

Transparent Hospital Pricing Exposes Wild Fluctuation, Even Within Miles (KHN)

By Harriet Blair Rowan, Kaiser Health News The federal government’s new rule requiring hospitals to post prices for their services is intended to allow patients to shop around and compare prices, a step toward price transparency that has generated praise and skepticism. Kaiser Health News examined the price lists — known in hospital lingo as “chargemasters” — of the largest acute care hospitals in several large cities. Prices varied widely on some basic procedures, even for basic charges. For instance, the list price on a liter of basic saline solution for intravenous use ranged from $56 to $472.50, nearly seven times as much. A brain MRI with contrast was priced from $1,7210 to $8,800 at the hospitals. And they varied widely even when comparing nearby hospitals. The new rule mandates that the chargemasters be available on the hospital website in a machine-readable format, but not all hospitals make them easy to find, and understanding them is a bigger obstacle. (Story continues below.) KHN senior correspondent Julie Appleby and California Healthline’s Barbara Feder Ostrov recently wrote about this new rule and found price lists befuddling to most anyone without an advanced medical degree. This story first appeared on California Healthline, and later on Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

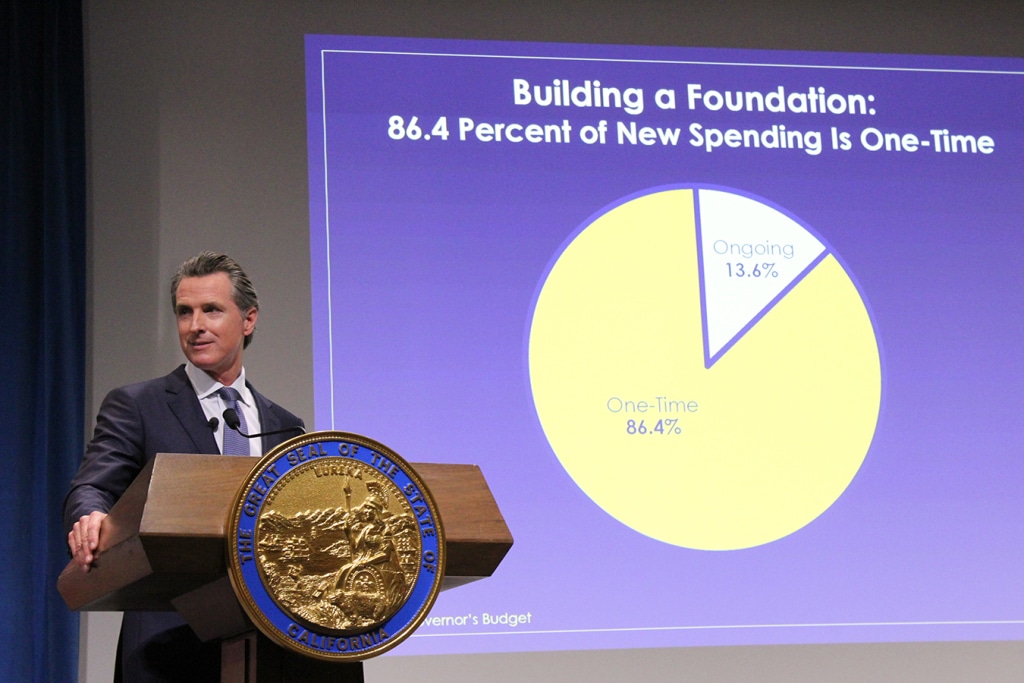

Analysis: Can States Fix The Disaster Of American Healthcare? (KHN)

By Elisabeth Rosenthal, Kaiser Health News Last week, California’s new governor, Gavin Newsom, promised to pursue a smörgåsbord of changes to his state’s healthcare system: state negotiation of drug prices, a requirement that every Californian have health insurance, more assistance to help middle-class Californians afford it and healthcare for undocumented immigrants up to age 26. The proposals fell short of the sweeping government-run single-payer plan Newsom had supported during his campaign — a system in which the state government would pay all the bills and effectively control the rates paid for services. (Many California politicians before him had flirted with such an idea, before backing off when it was estimated that it could cost $400 billion a year.) But in firing off this opening salvo, Newsom has challenged the notion that states can’t meaningfully tackle healthcare on their own. And he’s not alone. A day later, Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington proposed that his state offer a public plan, with rates tied to those of Medicare, to compete with private offerings. New Mexico is considering a plan that would allow any resident to buy in to the state’s Medicaid program. And this month, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York announced a plan to expand healthcare access to uninsured, low-income residents of the city, including undocumented immigrants. For over a decade, we’ve been waiting for Washington to solve our healthcare woes, with endless political wrangling and mixed results. Around 70 percent of Americans have said that healthcare is “in a state of crisis” or has “major problems.” Now, with Washington in total dysfunction, state and local politicians are taking up the baton. The legalization of gay marriage began in a few states and quickly became national policy. Marijuana legalization seems to be headed in the same direction. Could reforming healthcare follow the same trajectory? States have always cared about healthcare costs, but mostly insofar as they related to Medicaid, since that comes from state budgets. “The interesting new frontier is how states can use state power to change the healthcare system,” said Joshua Sharfstein, a vice dean at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a former secretary of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. He added that the new proposals “open the conversation about using the power of the state to leverage lower prices in healthcare generally.” Already states have proved to be a good crucible for experimentation. Massachusetts introduced “Romneycare,” a system credited as the model for the Affordable Care Act, in 2006. It now has the lowest uninsured rate in the nation, under 4 percent. Maryland has successfully regulated hospital prices based on an “all payer” system. It remains to be seen how far the West Coast governors can take their proposals. Businesses — pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, doctors’ groups — are likely to fight every step of the way to protect their financial interests. These are powerful constituents, with lobbyists and cash to throw around. The California Hospital Association came out in full support of Newsom’s proposals to expand insurance (after all, this would be good for hospitals’ bottom lines). It offered a slightly less enthusiastic endorsement for the drug negotiation program (which is less certain to help their budgets), calling it a “welcome” development. It’s notable that his proposals didn’t directly take on hospital pricing, even though many of the state’s medical centers are notoriously expensive. Giving the state power to negotiate drug prices for the more than 13 million patients either covered by Medicaid or employed by the state is likely to yield better prices for some. But pharma is an agile adversary and may well respond by charging those with private insurance more. The governor’s plan will eventually allow some employers to join in the negotiating bloc. But how that might happen remains unclear. The proposal by Washington Gov. Inslee to tie payment under the public option plans to Medicare’s rates drew “deep concern” from the Washington State Medical Association, which called those rates “artificially low, arbitrary and subject to the political whims of Washington, D.C.” On the bright side, if Newsom or Inslee succeeds in making healthcare more affordable and accessible for all with a new model, it will probably be replicated one by one in other states. That’s why I’m hopeful. In 2004, the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. conducted an exhaustive nationwide poll to select the greatest Canadian of all time. The top-10 list included Wayne Gretzky, Alexander Graham Bell and Pierre Trudeau. No. 1 is someone most Americans have never heard of: Tommy Douglas. Douglas, a Baptist minister and left-wing politician, was premier of Saskatchewan from 1944 to 1961. Considered the father of Canada’s health system, he arduously built up the components of universal healthcare in that province, even in the face of an infamous 23-day doctors’ strike. In 1962, the province implemented a single-payer program of universal, publicly funded health insurance. Within a decade, all of Canada had adopted it. The United States will presumably, sooner or later, find a model for healthcare that suits its values and its needs. But 2019 may be a time to look to the states for ideas rather than to the nation’s capital. Whichever state official pioneers such a system will certainly be regarded as a great American. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, and also ran in the New York Times. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

After Bitter Closure, Rural Texas Hospital Defies The Norm And Reopens (KHN)

By Charlotte Huff, Kaiser Health News Five months ago, the 6,500 residents of Crockett, Texas, witnessed a bit of a resurrection — at least in rural hospital terms. A little more than a year after the local hospital shut its doors, the 25-bed facility reopened its emergency department, inpatient beds and some related services, albeit on a smaller scale. Without a hospital, residents of Crockett, located 120 miles north of Houston, were 35 miles away along rural roads from the next closest hospital when a medical crisis struck, said Dr. Bob Grier, board president of the Houston County Hospital District, which is the county’s governmental authority that oversees Crockett, a public hospital. “Someone falls off the roof. A heart attack. A stroke. A diabetic coma. Start naming these rather serious things and health care is known for its golden hour,” he said. The late-July reopening of the newly named Crockett Medical Center makes it a bit of a unicorn in a state that has led nationally in rural hospital closures. Since January 2010, 17 of the 94 shuttered hospitals have been in Texas, including two that closed in December, according to data from the University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. But Crockett’s story also reflects some of the challenges faced by rural hospitals everywhere. Board members frequently have limited background in health care management and yet are responsible for making financial decisions. Add to that mix a Lone Star State resistance to raising local property taxes. An effort to increase the county’s 15 cents per $100 property valuation for the hospital district has been defeated twice since the hospital closed. And a small rural hospital like Crockett’s has “no leverage” when negotiating reimbursement rates with insurers, Grier repeatedly points out. The tough reality is that too many rural hospitals in Texas and elsewhere, when negotiating with insurers and other financial players, “are almost always negotiating from weakness and sometimes from literally leaning out over the edge of the [survival] cliff,” agreed Dr. Nancy Dickey, executive director of the A&M Rural and Community Health Institute at Texas A&M Health Science Center. Rural communities must think more creatively about how to meet at least some of their health needs without a traditional hospital, whether it’s forming partnerships with nearby towns or expanding telemedicine, Dickey said. “There is little doubt in my mind that many of these communities are going to see their hospitals close,” she said, “and are not going to be able to make an economic case to reopen them.” The A&M institute, which in December published a report looking at these challenges for three Texas communities, recently landed a $4 million, five-year federal grant to help rural hospitals nationwide keep their doors open or find other ways to maintain local health care. Demographics And Decisions The financial headwinds have been particularly fierce in Texas, one of 14 states that has not expanded Medicaid eligibility after the passage of the Affordable Care Act. “That makes a huge difference,” said John Henderson, chief executive officer of the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, known in Texas rural circles as TORCH. “But that doesn’t change the reality that we aren’t going to do it.” Leading up to the state’s biennial legislative session, which begins in January, rural leaders are making the case that state legislators need to take steps to bolster the state’s 161 rural hospitals, starting with rectifying underpayments for Medicaid patients. As the state’s program has transitioned to managed care, over time reimbursements have shrunk to the point that rural hospitals are losing as much as $60 million annually, according to TORCH officials, who cite state data. They also support a congressional bill, HR 5678, that would make it easier for rural hospitals to close their inpatient beds but retain some services, such as an emergency room and primary care clinic. Under current federal regulations, facilities that make such a move are no longer considered a hospital and can’t be reimbursed by Medicare and Medicaid at hospital rates, which are often higher than payments to clinics or individual doctors. Those lower rates make it harder for stripped-down facilities to keep up their operations, said Don McBeath, TORCH’s director of government relations. Crockett’s hospital, then called Timberlands Healthcare, abruptly shut down in summer 2017 after just a few weeks’ notice from its management company, Texas-based Little River Healthcare. Little River, which was also the subject of an analysis by Modern Healthcare that showed several of its hospitals engaged in unusually high laboratory billing for out-of-state patients, has since filed for bankruptcy. Two other rural hospitals affiliated with Little River closed their doors in December As it struggled to stay open, Crockett’s hospital had been treating a population that was increasingly poor and aging, according to Texas A&M’s report. The researchers describe in the report — Crockett is “community 1” among three communities featured — that the hospital was overstaffed with more than 200 employees given its daily average census of three hospitalized patients. Also, they wrote, board members should have more closely questioned the management company. The board said they were given data at each meeting, “but that data did not suggest the imminent demise of the hospital,” the report’s authors wrote. Fighting The Closure Tide Leaders in Crockett tried to capture the interest of other hospital systems to reopen and manage the facility, without success, Grier said. Along with staffers losing their jobs, the community knew it would be more difficult to persuade people to relocate or retire to the area without a hospital nearby, he said. Every weekday at noon for weeks on end, a small group of two to 20 people gathered beneath the hospital’s front portico to pray for some avenue to reopen, Grier said. Then, as the odds looked increasingly long, they got a call out of the blue from two Austin-based doctors. “I feel God was involved,” Grier said. “They have told us that they were looking for some