‘John Doe’ Patients Sometimes Force Hospital Staff To Play Detective (KHN)

By Susan Abram and Heidi de Marco, Kaiser Health News The 50-something man with a shaved head and brown eyes was unresponsive when the paramedics wheeled him into the emergency room. His pockets were empty: no wallet, no cellphone, not a single scrap of paper that might reveal his identity to the nurses and doctors working to save his life. His body lacked any distinguishing scars or tattoos. Almost two years after he was hit by a car on busy Santa Monica Boulevard in January 2017 and transported to Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center with a devastating brain injury, no one had come looking for him or reported him missing. The man died in the hospital, still a John Doe. Hospital staffs sometimes must play detective when an unidentified patient arrives for care. Establishing identity helps avoid the treatment risks that come with not knowing a patient’s medical history. And they strive to find next of kin to help make medical decisions. “We’re looking for a surrogate decision-maker, a person who can help us,” said Jan Crary, supervising clinical social worker at L.A. County+USC, whose team is frequently called on to identify unidentified patients. The hospital also needs a name to collect payment from private insurance or government health programs such as Medicaid or Medicare. But federal privacy laws can make uncovering a patient’s identity challenging for staff members at hospitals nationwide. At L.A. County+USC, social workers pick through personal bags and clothing, scroll through cellphones that are not password-protected for names and numbers of family or friends, and scour receipts or crumpled pieces of paper for any trace of a patient’s identity. They quiz the paramedics who brought in the patient or the dispatchers who took the call. They also make note of any tattoos and piercings, and even try to track down dental records. It’s more difficult to check fingerprints, because that’s done through law enforcement, which will get involved only if the case has a criminal aspect, Crary said. Unidentified patients are often pedestrians or cyclists who left their IDs at home and were struck by vehicles, said Crary. They might also be people with severe cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer’s, patients in a psychotic state or drug users who have overdosed. The hardest patients to identify are ones who are socially isolated, including homeless people — whose admissions to hospitals have grown sharply in recent years. In the past three years, the number of patients who arrived unidentified at L.A. County+USC ticked up from 1,131 in 2016 to 1,176 in 2018, according to data provided by the hospital. If a patient remains unidentified for too long, the staff at the hospital will make up an ID, usually beginning with the letter “M” or “F” for gender, followed by a number and a random name, Crary said. Jan Crary, supervising clinical social worker at Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center, leads a team who increasingly must play detective when patients cannot be identified. Other hospitals resort to similar tactics to ease billing and treatment. In Nevada, hospitals have an electronic system that assigns unidentified patients a “trauma alias,” said Christopher Lake, executive director of community resilience at the Nevada Hospital Association. The deadly mass shooting at a Las Vegas concert in October 2017 presented a challenge for local hospitals who sought to identify the victims. Most concertgoers were wearing wristbands with scannable chips that contained their names and credit card numbers so they could buy beer and souvenirs. On the night of the shooting, the final day of a three-day event, many patrons were so comfortable with the wristbands that they carried no wallets or purses. More than 800 people were injured that night and rushed to numerous hospitals, none of which were equipped with the devices to scan the wristbands. Staff at the hospitals worked to identify patients by their tattoos, scars or other distinguishing features, as well as photographs on social media, said Lake. But it was a struggle, especially for smaller hospitals, he said. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), a federal law intended to ensure the privacy of personal medical data, can sometimes make an identification more arduous because a hospital may not want to release information on unidentified patients to people inquiring about missing persons. In 2016, a man with Alzheimer’s disease was admitted to a New York hospital through the emergency department as an unidentified patient and assigned the name “Trauma XXX.” Police and family members inquired about him at the hospital several times but were told he was not there. After a week — during which hundreds of friends, family members and law enforcement officials searched for the man — a doctor who worked at the hospital saw a news story about him on television and realized he was the unidentified patient. Hospital officials later told the man’s son that because he had not explicitly asked for “Trauma XXX,” they could not give him information that might have helped him identify his father. Prompted by that mix-up, the New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse drafted a set of guidelines for hospital administrators who receive information requests about missing persons from police or family members. The guidelines include about two dozen steps for hospitals to follow, including notifying the front desk, entering detailed physical descriptions into a database, taking DNA samples and monitoring emails and faxes about missing persons. California guidelines stipulate that if a patient is unidentified and cognitively incapacitated, “the hospital may disclose only the minimum necessary information that is directly relevant to locating a patient’s next-of-kin, if doing so is in the best interest of the patient.” At L.A. County+USC, most John Does are quickly identified: They either regain consciousness or, as in a majority of cases, friends or relatives call asking about them, Crary said. Still, the hospital does not always succeed. From 2016 to 2018, 10 John and Jane Does remained unidentified during their stays at L.A. County+USC. Some died at the hospital; others

Short-Staffed Nursing Homes See Drop In Medicare Ratings (KHN)

By Jordan Rau and Elizabeth Lucas, Kaiser Health News The federal government accelerated its crackdown on nursing homes that go days without a registered nurse by downgrading the rankings of a tenth of the nation’s homes on Medicare’s consumer website, new records show. In its update in April to Nursing Home Compare, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gave its lowest star rating for staffing — one star on its five-star scale — to 1,638 homes. Most were downgraded because their payroll records reported no registered-nurse hours at all for four days or more, while the remainder failed to submit their payroll records or sent data that couldn’t be verified through an audit. “Once you’re past four days [without registered nursing], it’s probably beyond calling in sick,” said David Grabowski, a health policy professor at Harvard Medical School. “It’s probably a systemic problem.” It was a tougher standard than Medicare had previously applied, when it demoted nursing homes with seven or more days without a registered nurse. “Nurse staffing has the greatest impact on the quality of care nursing homes deliver, which is why CMS analyzed the relationship between staffing levels and outcomes,” the agency announced in March. “CMS found that as staffing levels increase, quality increases.” The latest batch of payroll records, released in April, shows that even more nursing homes fell short of Medicare’s requirement that a registered nurse be on-site at least eight hours every day. Over the final three months of 2018, 2,633 of the nation’s 15,563 nursing homes reported that for four or more days, registered nurses worked fewer than eight hours, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis. Those facilities did not meet Medicare’s requirement even after counting nurses whose jobs are primarily administrative. CMS has been alarmed at the frequency of understaffing of registered nurses — the most highly trained category of nurses in a home — since the government last year began requiring homes to submit payroll records to verify staffing levels. Before that, Nursing Home Compare relied on two-week snapshots nursing homes reported to health inspectors when they visited — a method officials worried was too easy to manipulate. The records show staffing on weekends is often particularly anemic. CMS’ demotion of ratings on staffing is not as severe as it might seem, however. More than half of those homes were given a higher rating than one star for their overall assessment after CMS weighed inspection results and the facilities’ own measurement of residents’ health improvements. That overall rating is the one that garners the most attention on Nursing Home Compare and that some hospitals use when recommending where discharged patients might go. Of the 1,638 demoted nursing homes, 277 were rated as average in overall quality (three stars), 175 received four stars, and 48 received the top rating of five stars. Still, CMS’ overall changes to how the government assigns stars drew protests from nursing home groups. The American Health Care Association, a trade group for nursing homes, calculated that 36% of homes saw a drop in their ratings while 15% received improved ratings. “By moving the scoring ‘goal posts’ for two components of the Five-Star system,” the association wrote, “CMS will cause more than 30 percent of nursing centers nationwide to lose one or more stars overnight — even though nothing changed in staffing levels and in quality of care, which is still being practiced and delivered every day.” The association said in an email that the payroll records might exaggerate the absence of staff through unintentional omissions that homes make when submitting the data or because of problems on the government’s end. The association said it had raised concerns that salaried nurses face obstacles in recording time they worked above 40 hours a week. Also, the association added, homes must deduct a half-hour for every eight-hour shift for a meal break, even if the nurse worked through it. “Some of our member nursing homes have told us that their data is not showing up correctly on Nursing Home Compare, making it appear that they do not have the nurses and other staff that they in fact do have on duty,” LeadingAge, an association of nonprofit medical providers including nursing homes, said last year. Kaiser Health News has updated its interactive nursing home staffing tool with the latest data. You can use the tool to see the rating Medicare assigns to each facility for its registered nurse staffing and overall staffing levels. The tool also shows KHN-calculated ratios of patients to direct-care nurses and aides on the best- and worst-staffed days. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

As Syphilis Invades Rural America, A Fraying Health Safety Net Is Failing To Stop It (KHN)

By Lauren Weber, Kaiser Health News When Karolyn Schrage first heard about the “dominoes gang” in the health clinic she runs in Joplin, Mo., she assumed it had to do with pizza. Turns out it was a group of men in their 60s and 70s who held a standing game night — which included sex with one another. They showed up at her clinic infected with syphilis. That has become Schrage’s new normal. Pregnant women, young men and teens are all part of the rapidly growing number of syphilis patients coming to the Choices Medical Services clinic in the rural southwestern corner of the state. She can barely keep the antibiotic treatment for syphilis, penicillin G benzathine, stocked on her shelves. Public health officials say rural counties across the Midwest and West are becoming the new battleground. While syphilis is still concentrated in cities such as San Francisco, Atlanta and Las Vegas, its continued spread into places like Missouri, Iowa, Kansas and Oklahoma creates a new set of challenges. Compared with urban hubs, rural populations tend to have less access to public health resources, less experience with syphilis and less willingness to address it because of socially conservative views toward homosexuality and nonmarital sex. In Missouri, the total number of syphilis patients has more than quadrupled since 2012 — jumping from 425 to 1,896 cases last year — according to a Kaiser Health News analysis of new state health data. Almost half of those are outside the major population centers and typical STD hot spots of Kansas City, St. Louis and its adjacent county. Syphilis cases surged at least eightfold during that period in the rest of the state. At Choices Medical Services, Schrage has watched the caseload grow from five cases to 32 in the first quarter of 2019 alone compared with the same period last year. “I’ve not seen anything like it in my history of doing sexual health care,” she said. Back in 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had a plan to eradicate the sexually transmitted disease that totaled over 35,000 cases nationwide that year. While syphilis can cause permanent neurological damage, blindness or even death, it is both treatable and curable. By focusing on the epicenters clustered primarily throughout the South, California and in major urban areas, the plan seemed within reach. Instead, U.S. cases topped 101,500 in 2017 and are continuing to rise along with other sexually transmitted diseases. Syphilis is back in part because of increasing drug use, but health officials are losing the fight because of a combination of cuts in national and state health funding and crumbling public health infrastructure. “It really is astounding to me that in the modern Western world we are dealing with the epidemic that was almost eradicated,” said Schrage. Grappling With The Jump Craig Highfill, who directs Missouri’s field prevention efforts for the Bureau of HIV, STD and Hepatitis, has horror stories about how syphilis can be misunderstood. “Oh, no, honey, only hookers get syphilis,” he said one rural doctor told a patient who asked if she had the STD after spotting a lesion. In small towns, younger patients fear that their local doctor — who may also be their Sunday school teacher or basketball coach — may call their parents. Others don’t want to risk the receptionist at their doctor’s office gossiping about their diagnosis. Some men haven’t told family members they’re having sex with other men. And still more have no idea their partner may have cheated on them — and their doctors don’t want to ask, according to Highfill. It’s even hard to expect providers who haven’t seen a case of syphilis in their lifetime to automatically recognize the hallmarks of what is often called the “great imitator,” Highfill said. Syphilis can manifest differently among patients, but frequently shows up for a few weeks as lesions or rashes — often dismissed by doctors who aren’t expecting to see the disease. Since 2000, the current syphilis epidemic was most prevalent among men having sex with men. Starting in 2013, public health officials began seeing an alarming jump in the number of women contracting syphilis, which is particularly disturbing considering the deadly effects of congenital syphilis — when the disease is passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus. That can cause miscarriage, stillbirth or birth deformities. Among those rising numbers of women contracting syphilis and the men who were their partners, self-reported use of methamphetamines, heroin or other intravenous drugs continues to grow, according to the CDC. Public health officials suggest that increased drug use — which can result in a pattern of risky sex or trading sex for drugs — worsens the outbreaks. That perilous trend is playing out particularly in rural Missouri, argues Dr. Hilary Reno, an assistant professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis who is researching syphilis transmission and drug use in the state. Tracking cases from 2015 through June 2018, she found that more than half of patients outside of the major metropolitan areas of Kansas City and St. Louis reported using drugs. Less Money, More Problems Federal funding for STD prevention has stayed relatively flat since 2003, with $157.3 million allocated for fiscal year 2018. But that amounts to a nearly 40% decrease in purchasing power over that time, according to the National Coalition of STD Directors. In Missouri, CDC annual funding has been cut by over $354,000 from 2012 to 2018 — a 17% decrease even as the number of cases quadrupled, Highfill said. Iowa, too, has seen its STD funding cut by $82,000 over the past decade, according to Iowa Department of Health’s STD program manager George Walton. “It is very difficult to get ahead of an epidemic when case counts are steadily — sometimes rapidly — increasing and your resources are at best stagnant,” Walton said. “It just becomes overwhelming.” Highfill bemoaned that legislatures in Texas, Oregon and New York have all allocated state money to raise

Death By 1,000 Clicks: Where Electronic Health Records Went Wrong (KHN)

By Fred Schulte, Kaiser Health News and Erika Fry, Fortune The pain radiated from the top of Annette Monachelli’s head, and it got worse when she changed positions. It didn’t feel like her usual migraine. The 47-year-old Vermont attorney turned innkeeper visited her local doctor at the Stowe Family Practice twice about the problem in late November 2012, but got little relief. Two months later, Monachelli was dead of a brain aneurysm, a condition that, despite the symptoms and the appointments, had never been tested for or diagnosed until she turned up in the emergency room days before her death. Monachelli’s husband sued Stowe, the federally qualified health center the physician worked for. Owen Foster, a newly hired assistant U.S. attorney with the District of Vermont, was assigned to defend the government. Though it looked to be a standard medical malpractice case, Foster was on the cusp of discovering something much bigger — what his boss, U.S. Attorney Christina Nolan, calls the “frontier of health care fraud” — and prosecuting a first-of-its-kind case that landed the largest-ever financial recovery in Vermont’s history. Foster began with Monachelli’s medical records, which offered a puzzle. Her doctor had considered the possibility of an aneurysm and, to rule it out, had ordered a head scan through the clinic’s software system, the government alleged in court filings. The test, in theory, would have caught the bleeding in Monachelli’s brain. But the order never made it to the lab; it had never been transmitted. The software in question was an electronic health records system, or EHR, made by eClinicalWorks (eCW), one of the leading sellers of record-keeping software for physicians in America, currently used by 850,000 health professionals in the U.S. It didn’t take long for Foster to assemble a dossier of troubling reports — Better Business Bureau complaints, issues flagged on an eCW user board, and legal cases filed around the country — suggesting the company’s technology didn’t work quite the way it said it did. Until this point, Foster, like most Americans, knew next to nothing about electronic medical records, but he was quickly amassing clues that eCW’s software had major problems — some of which put patients, like Annette Monachelli, at risk. Damning evidence came from a whistleblower claim filed in 2011 against the company. Brendan Delaney, a British cop turned EHR expert, was hired in 2010 by New York City to work on the eCW implementation at Rikers Island, a jail complex that then had more than 100,000 inmates. But soon after he was hired, Delaney noticed scores of troubling problems with the system, which became the basis for his lawsuit. The patient medication lists weren’t reliable; prescribed drugs would not show up, while discontinued drugs would appear as current, according to the complaint. The EHR would sometimes display one patient’s medication profile accompanied by the physician’s note for a different patient, making it easy to misdiagnose or prescribe a drug to the wrong individual. Prescriptions, some 30,000 of them in 2010, lacked proper start and stop dates, introducing the opportunity for under- or overmedication. The eCW system did not reliably track lab results, concluded Delaney, who tallied 1,884 tests for which they had never gotten outcomes. The District of Vermont launched an official federal investigation in 2015. The eCW spaghetti code was so buggy that when one glitch got fixed, another would develop, the government found. The user interface offered a few ways to order a lab test or diagnostic image, for example, but not all of them seemed to function. The software would detect and warn users of dangerous drug interactions, but unbeknownst to physicians, the alerts stopped if the drug order was customized. “It would be like if I was driving with the radio on and the windshield wipers going and when I hit the turn signal, the brakes suddenly didn’t work,” said Foster. The eCW system also failed to use the standard drug codes and, in some instances, lab and diagnosis codes as well, the government alleged. The case never got to a jury. In May 2017, eCW paid a $155 million settlement to the government over alleged “false claims” and kickbacks — one physician made tens of thousands of dollars — to clients who promoted its product. Despite the record settlement, the company denied wrongdoing; eCW did not respond to numerous requests for comment. If there is a kicker to this tale, it is this: The U.S. government bankrolled the adoption of this software — and continues to pay for it. Or we should say: You do. Which brings us to the strange, sad, and aggravating story that unfolds below. It is not about one lawsuit or a piece of sloppy technology. Rather, it’s about a trouble-prone industry that intersects, in the most personal way, with every one of our lives. It’s about a $3.7 trillion health care system idling at the crossroads of progress. And it’s about a slew of unintended consequences — the surprising casualties of a big idea whose time had seemingly come. The Virtual Magic Bullet Electronic health records were supposed to do a lot: make medicine safer, bring higher-quality care, empower patients, and yes, even save money. Boosters heralded an age when researchers could harness the big data within to reveal the most effective treatments for disease and sharply reduce medical errors. Patients, in turn, would have truly portable health records, being able to share their medical histories in a flash with doctors and hospitals anywhere in the country — essential when life-and-death decisions are being made in the ER. But 10 years after President Barack Obama signed a law to accelerate the digitization of medical records — with the federal government, so far, sinking $36 billion into the effort — America has little to show for its investment. KHN and Fortune spoke with more than 100 physicians, patients, IT experts and administrators, health policy leaders, attorneys, top government officials and representatives at more than a half-dozen EHR vendors, including

Shrinking Medicaid Rolls In Missouri And Tennessee Raise Flag On Vetting Process

By Phil Galewitz, Kaiser Health News Tangunikia Ward, a single mom of two who has been unemployed for the past couple of years, was shocked when her St. Louis family was kicked off Missouri’s Medicaid program without warning last fall. She found out only when taking her son, Mario, 10, to a doctor to be treated for ringworm. When Ward, 29, tried to contact the state to get reinstated, she said it took several weeks just to have her calls returned. Then she waited again for the state to mail her a long form to fill out attesting to her income and family size, showing that she was still eligible for the state-federal health insurance program for the poor. Mario, who is in third grade, missed much of school in December because Ward could not afford a doctor visit without Medicaid. His school would not let him return without a doctor’s note saying he was no longer infected. In January, with the help of lawyers from Legal Services of Eastern Missouri, she was able to get back on Medicaid, take her son to a doctor and return him to school. “It was a real struggle as it seemed like everyone was giving me the runaround,” Ward said. “I am upset because my son was out of school, and that pushed him behind.” Ward and her children are among tens of thousands of Medicaid enrollees who were dropped by Missouri and Tennessee last year as both states stepped up efforts to verify members’ eligibility. Last year, Medicaid enrollment there declined far faster than in other states, and most of those losing coverage are children, according to state data. State health officials say several factors, including the improved economy, are behind last year’s drop of 7 percent in Missouri and 9 percent in Tennessee. But advocates for the poor think the states’ efforts to weed out residents who are improperly enrolled, or the difficulty of re-enrolling, has led to people being forced off the rolls. For example, Tennessee sent packets to enrollees that could be as long as 47 pages to verify their re-enrollment. In Missouri, people faced hours-long waits on the state’s phone lines to get help in enrolling. Medicaid enrollment nationally was down about 1.5 percent from January to October last year, the latest enrollment data available from the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Herb Kuhn, president and chief executive of the Missouri Hospital Association, said the state’s efforts to verify Medicaid eligibility could be tied to an increase in the number of people without coverage that hospitals are seeing. “When we see over 50,000 children come off the Medicaid rolls, it raises some questions about whether the state is doing its verifications appropriately,” he said. “Those who are truly entitled to the service should get to keep it.” In 2018, Missouri Medicaid began automating its verification system for the state-federal insurance program for the poor. People who were identified as ineligible, for income or other reasons, were sent a letter asking them to provide updated documentation. Those who did not respond or could not prove their eligibility were dropped. The state does not know how many letters it sent or how many people responded, said Rebecca Woelfel, spokeswoman for the Missouri Department of Social Services, which oversees Medicaid. She said Missouri Medicaid enrollees were given 10 days to respond. Woelfel cited the new Medicaid eligibility system, the improved economy and Congress rescinding the federal tax penalty for people who lack insurance as factors behind the decline in enrollment. Missouri’s unemployment rate dropped from 3.7 percent in January 2018 to 3.1 percent in December as the number of unemployed people fell by about 17,000. Missouri Medicaid had almost 906,000 people enrolled as of December, down from more than 977,000 in January 2018, according to state data. About two-thirds of those enrolled are children or pregnant women. Timothy McBride, a health economist at Washington University in St. Louis who heads a Missouri Medicaid advisory board, said the state’s Medicaid eligibility system has made it too difficult for people to stay enrolled. Since low-income people move or may be homeless, their mailing addresses may be inaccurate. Plus, many don’t read their mail or may not understand what was required to stay enrolled, he added. “I worry some people are still eligible but just did not respond, and the next time they need health care they will show up with their Medicaid card and find out they are not covered,” McBride said. Tennessee’s Medicaid enrollment fell from 1.48 million in January 2018 to 1.35 million in December, according to state data. Tennessee Medicaid spokeswoman Kelly Gunderson credits a healthy job market. The state’s unemployment rate was relatively stable last year at under 4 percent. “Tennessee is experiencing a state economy that continues to increase at what appears to be near-historic rates, which is positively impacting Tennesseans’ lives and, in some cases, decreasing their need to access health insurance through the state’s Medicaid” program and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), she said. She added that the state has a “robust appeals process” for anyone who was found ineligible by the state’s reverification system. The Tennessee Justice Center, an advocacy group, has worked with hundreds of families in the past year trying to restore their Medicaid coverage. The verification process will make “Medicaid rolls smaller and saves money, and that’s a poor way for the state to measure success,” said Michele Johnson, executive director of the nonprofit group. “But it’s penny-wise and pound-foolish” because it leads to people showing up at emergency rooms without coverage — and hospitals have to pass on those costs to everyone else. After rapid growth since 2014, when the Affordable Care Act expanded health insurance coverage to millions of Americans, Medicaid enrollment nationally started to fall, declining from 74 million in January 2018 to about 73 million in October, according to the latest enrollment data released by CMS. Missouri and Tennessee are among 17

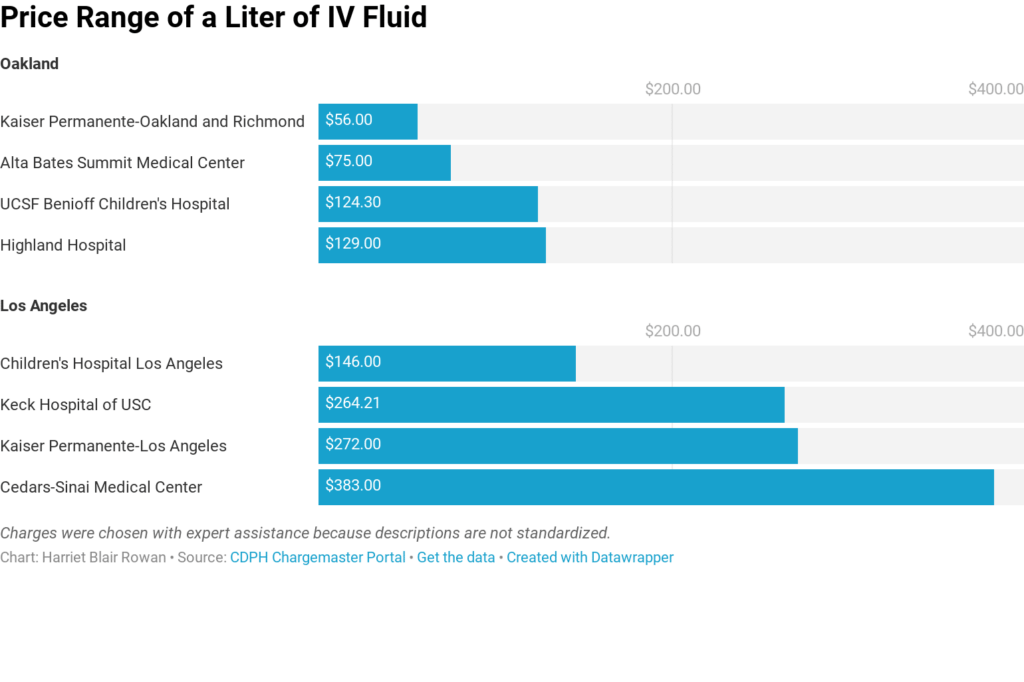

Transparent Hospital Pricing Exposes Wild Fluctuation, Even Within Miles (KHN)

By Harriet Blair Rowan, Kaiser Health News The federal government’s new rule requiring hospitals to post prices for their services is intended to allow patients to shop around and compare prices, a step toward price transparency that has generated praise and skepticism. Kaiser Health News examined the price lists — known in hospital lingo as “chargemasters” — of the largest acute care hospitals in several large cities. Prices varied widely on some basic procedures, even for basic charges. For instance, the list price on a liter of basic saline solution for intravenous use ranged from $56 to $472.50, nearly seven times as much. A brain MRI with contrast was priced from $1,7210 to $8,800 at the hospitals. And they varied widely even when comparing nearby hospitals. The new rule mandates that the chargemasters be available on the hospital website in a machine-readable format, but not all hospitals make them easy to find, and understanding them is a bigger obstacle. (Story continues below.) KHN senior correspondent Julie Appleby and California Healthline’s Barbara Feder Ostrov recently wrote about this new rule and found price lists befuddling to most anyone without an advanced medical degree. This story first appeared on California Healthline, and later on Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

After Bitter Closure, Rural Texas Hospital Defies The Norm And Reopens (KHN)

By Charlotte Huff, Kaiser Health News Five months ago, the 6,500 residents of Crockett, Texas, witnessed a bit of a resurrection — at least in rural hospital terms. A little more than a year after the local hospital shut its doors, the 25-bed facility reopened its emergency department, inpatient beds and some related services, albeit on a smaller scale. Without a hospital, residents of Crockett, located 120 miles north of Houston, were 35 miles away along rural roads from the next closest hospital when a medical crisis struck, said Dr. Bob Grier, board president of the Houston County Hospital District, which is the county’s governmental authority that oversees Crockett, a public hospital. “Someone falls off the roof. A heart attack. A stroke. A diabetic coma. Start naming these rather serious things and health care is known for its golden hour,” he said. The late-July reopening of the newly named Crockett Medical Center makes it a bit of a unicorn in a state that has led nationally in rural hospital closures. Since January 2010, 17 of the 94 shuttered hospitals have been in Texas, including two that closed in December, according to data from the University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. But Crockett’s story also reflects some of the challenges faced by rural hospitals everywhere. Board members frequently have limited background in health care management and yet are responsible for making financial decisions. Add to that mix a Lone Star State resistance to raising local property taxes. An effort to increase the county’s 15 cents per $100 property valuation for the hospital district has been defeated twice since the hospital closed. And a small rural hospital like Crockett’s has “no leverage” when negotiating reimbursement rates with insurers, Grier repeatedly points out. The tough reality is that too many rural hospitals in Texas and elsewhere, when negotiating with insurers and other financial players, “are almost always negotiating from weakness and sometimes from literally leaning out over the edge of the [survival] cliff,” agreed Dr. Nancy Dickey, executive director of the A&M Rural and Community Health Institute at Texas A&M Health Science Center. Rural communities must think more creatively about how to meet at least some of their health needs without a traditional hospital, whether it’s forming partnerships with nearby towns or expanding telemedicine, Dickey said. “There is little doubt in my mind that many of these communities are going to see their hospitals close,” she said, “and are not going to be able to make an economic case to reopen them.” The A&M institute, which in December published a report looking at these challenges for three Texas communities, recently landed a $4 million, five-year federal grant to help rural hospitals nationwide keep their doors open or find other ways to maintain local health care. Demographics And Decisions The financial headwinds have been particularly fierce in Texas, one of 14 states that has not expanded Medicaid eligibility after the passage of the Affordable Care Act. “That makes a huge difference,” said John Henderson, chief executive officer of the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, known in Texas rural circles as TORCH. “But that doesn’t change the reality that we aren’t going to do it.” Leading up to the state’s biennial legislative session, which begins in January, rural leaders are making the case that state legislators need to take steps to bolster the state’s 161 rural hospitals, starting with rectifying underpayments for Medicaid patients. As the state’s program has transitioned to managed care, over time reimbursements have shrunk to the point that rural hospitals are losing as much as $60 million annually, according to TORCH officials, who cite state data. They also support a congressional bill, HR 5678, that would make it easier for rural hospitals to close their inpatient beds but retain some services, such as an emergency room and primary care clinic. Under current federal regulations, facilities that make such a move are no longer considered a hospital and can’t be reimbursed by Medicare and Medicaid at hospital rates, which are often higher than payments to clinics or individual doctors. Those lower rates make it harder for stripped-down facilities to keep up their operations, said Don McBeath, TORCH’s director of government relations. Crockett’s hospital, then called Timberlands Healthcare, abruptly shut down in summer 2017 after just a few weeks’ notice from its management company, Texas-based Little River Healthcare. Little River, which was also the subject of an analysis by Modern Healthcare that showed several of its hospitals engaged in unusually high laboratory billing for out-of-state patients, has since filed for bankruptcy. Two other rural hospitals affiliated with Little River closed their doors in December As it struggled to stay open, Crockett’s hospital had been treating a population that was increasingly poor and aging, according to Texas A&M’s report. The researchers describe in the report — Crockett is “community 1” among three communities featured — that the hospital was overstaffed with more than 200 employees given its daily average census of three hospitalized patients. Also, they wrote, board members should have more closely questioned the management company. The board said they were given data at each meeting, “but that data did not suggest the imminent demise of the hospital,” the report’s authors wrote. Fighting The Closure Tide Leaders in Crockett tried to capture the interest of other hospital systems to reopen and manage the facility, without success, Grier said. Along with staffers losing their jobs, the community knew it would be more difficult to persuade people to relocate or retire to the area without a hospital nearby, he said. Every weekday at noon for weeks on end, a small group of two to 20 people gathered beneath the hospital’s front portico to pray for some avenue to reopen, Grier said. Then, as the odds looked increasingly long, they got a call out of the blue from two Austin-based doctors. “I feel God was involved,” Grier said. “They have told us that they were looking for some

Short-Term Health Plans Hold Savings For Consumers, Profits For Brokers And Insurers (KHN)

By Julie Appleby, Kaiser Health News Sure, they’re less expensive for consumers, but short-term health policies have another side: They’re highly profitable for insurers and offer hefty sales commissions. Driven by rising premiums for Affordable Care Act plans, interest in short-term insurance is growing, boosted by Trump administration actions to ease Obama-era restrictions and possibly make federal subsidies available to consumers to purchase them. That’s good news for brokers, who often see commissions on such policies hit 20 percent or more. On a policy costing $200 a month, for example, that could translate to a $40 payment each month. By contrast, ACA plan commissions, which are often flat dollar amounts rather than a percentage of premium, can range from zero to $20 per enrollee per month. “Customers are paying less and I’m making more,” said Cindy Holtzman, a broker in Woodstock, Ga., who said she gets 20 percent on short-term plan commissions. Large online brokers also are eagerly eyeing the market. Ehealth, one such firm, will “continue to shift our focus to selling short-term plans and non-ACA insurance packages,” CEO Scott Flanders told investors in October. The firm saw an 18 percent annual jump in enrollment in short-term plans this year, he added. Insurers, too, see strong profits from plans because they generally pay out very little toward medical care when compared with the more comprehensive ACA plans. Still, some agents like Holtzman have mixed feelings about selling the plans, because they offer skimpier coverage than ACA insurance. One 58-year-old client of Holtzman’s wanted one, but he had health problems. She also learned his income qualified him for an ACA subsidy, which currently cannot be used to purchase short-term coverage. “There’s no way I would have considered a short-term plan for him,” she said. “I found him an ACA plan for $360 a month with a reduced deductible.” (A federal district court judge in Texas issued a ruling Dec. 14 striking down the ACA, which would among other things impact the requirements of ACA coverage and subsidies. The decision is expected to face appeal.) Short-term plans can be far less expensive than ACA plans because they set annual or lifetime payment limits. Most exclude people with medical conditions, they often don’t cover prescription drugs, and policies exclude in fine print some conditions or treatments. Injuries sustained in school sports programs, for example, often are not covered. (These plans can be purchased at any time throughout the year, which is different than plans sold through the federal marketplaces. The open enrollment period for those ACA plans in most states ends Dec. 15.) Consequently, insurers providing short-term plans don’t have to pay as many medical bills, so they have more money left over for profits. In forms filed with state regulators, Independence American Insurance Co. in Ohio shows it expects 60 percent of its premium revenue to be spent on its enrollees’ medical care. The remaining 40 percent can go to profits, executive salaries, marketing and commissions. A 2016 report from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners showed that, on average, short-term plans paid out about 67 percent of their earnings on medical care. That compares with ACA plans, which are required under the law to spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on medical claims. Short-term plans have long been sold mainly as a stopgap measure for people between jobs or school coverage. While exact figures are not available, brokers say interest dropped when the ACA took effect in 2014 because many people got subsidies to buy ACA plans and having a short-term plan did not exempt consumers from the law’s penalty for not carrying insurance. But this year it ticked up again after Congress eliminated the penalty for 2019 coverage. At the same time, the premiums for ACA plans rose on average more than 30 percent. “If I don’t want someone to walk out of the office with nothing at all because of cost, that’s when I will bring up short-term plans,” said Kelly Rector, president of Denny & Associates, an insurance sales brokerage in O’Fallon, a suburb of St. Louis. “But I don’t love the plans because of the risk.” The Obama administration limited short-term plans to 90-day increments to reduce the number of younger or healthier people who would leave the ACA market. That rule, the Trump administration complained, forced people to reapply every few months and risk rejection by insurers if their health had declined. This summer, the administration finalized new rules allowing insurers to offer short-term plans for up to 12 months — and gave them the option to allow renewals for up to three years. States can be more restrictive or even bar such plans altogether. Administration officials estimate short-term plans could be half the cost of the more comprehensive ACA insurance and draw 600,000 people to enroll in 2019, with 100,000 to 200,000 of those dropping ACA coverage to do so. And recent guidance to states says they could seek permission to allow federal subsidies to be used for short-term plans. Currently, those subsidies apply only to ACA-compliant plans. Granting subsidies for short-term plans “would mean tax dollars are not only subsidizing commissions, but also executive salaries and marketing budgets,” said Sabrina Corlette of Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms. No state has yet applied to do that. For now, brokers are focusing on getting their clients into some kind of coverage for next year. Commissions on both ACA and short-term plans are getting their attention. After several years of declining commissions for ACA plans — with some carriers cutting them altogether a couple of years ago — brokers say they are seeing a bit of a rebound. Among Colorado ACA insurers, “it’s gone from about $14 to $16 per enrollee [a month] to $16 to $18,” said Louise Norris, a health policy writer and co-owner of an insurance brokerage. Rector, in Missouri, said an insurer that last year paid no commissions has reinstated them for 2019 coverage. For her, that doesn’t really

In Grandma’s Stocking: An Apple Watch To Monitor Falls, Track Heart Rhythms

By Rachel Bluth, Kaiser Health News For more than a decade, the latest Apple products have been the annual must-have holiday gift for the tech-savvy. That raises the question: Is the newest Apple Watch on your list — either to give or receive — this year? At first glance, the watch appears to be an ideal present for Apple’s most familiar market: the hip early adopters. Its promotional website is full of svelte young people stretching into yoga poses, kickboxing and playing basketball. But when Apple unveiled its latest model in September — the Series 4, which starts at $399 — it was clear it was expanding its target audience. This Apple Watch includes new features designed to detect falls and heart problems. With descriptions like “part guardian, part guru” and “designed to improve your health … and powerful enough to protect it,” the tech giant signaled its move toward preventive health and a much wider demographic. “The health care market is obviously important to Apple,” Andy Hargreaves, an Apple analyst with KeyBanc Capital Markets, wrote in an email. The fall prevention and electrocardiogram apps are a “play to sell people more stuff” and bring health-monitoring apps beyond just “fitness people” to baby boomers who want to keep themselves and their parents healthy, he added. This watch could be a perfect present for those older people, said Laura Martin, a senior analyst with Needham. “People who wore watches their whole lives, plus fall monitoring?” Martin said. “Voilà! It creates another on-ramp for another consumer in the Apple ecosystem.” The Inner Workings The fall-monitoring app uses sensors in the watchband, which are automatically enabled for people 65 and older after they input their age. These sensors track and record the user’s movements, and note if the wearer’s gait becomes unsteady. If a fall is detected, the watch sends its wearer a notification. If the wearer doesn’t respond within a minute by tapping a button on the watch to deactivate this signal, emergency services will be alerted that the wearer needs help. That minute also gives the wearer time to prevent false alarms, such as a dropped watch. Many geriatricians and medical experts agree that this app could help older consumers. Falls can cause fractured hips and head injuries, but even fear of falling can prevent older people from living on their own or participating in activities. Fall deaths in the U.S. increased 30 percent for older adults in the past decade, and 3 million older people go to the emergency room for fall injuries each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Armin Shahrokni, an internist with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center who describes himself as “tech-savvy,” is excited that older patients might get into wearable technology. “In older cancer patients, my area of expertise, all the chemo can make them fall more,” he said, making detecting falls and balance important. The other app, the ECG monitoring app, also uses sensors in the wristband to monitor a patient’s heartbeat and send alerts if it gets too fast or too slow. Specifically, the app is meant to detect atrial fibrillation, which is a type of arrhythmia, also described as a problem with the speed or rhythm of the heartbeat. Here is how the app works: The watch’s sensors can detect a heart rhythm in 30 seconds, creating a “waveform” readout. It also allows the user to note how they are feeling — lightheaded, winded, full of energy — at that moment. This combination, according to Apple, will help people have better conversations with their doctors about symptoms and heart patterns. The Food and Drug Administration cleared this function for people 22 or older. However, it’s rare for anyone younger than 50 to be diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, noted Eric Topol, a cardiologist at the Scripps Research Institute. Doctors have expressed concern that scores of panicked Apple Watch users would flood emergency rooms with every heart rhythm notification and blip. “It’s mass use of a tool, and with that is going to come lots of unintended consequences,” Topol said. “It’ll lead to a lot of anxiety and expense and additional testing, and even then some people will get blood thinners inappropriately,” he added. “This is the opposite of individualized medicine, where you are using something on exactly, precisely the right person,” Topol said. Wearables Unleashed The watch represents the beginning of what analysts agree will be a wave of new health apps and wearable health trackers. Consumers can expect more ways to track vital signs, like blood sugar, and more apps that will use those numbers to help people prevent medical emergencies, said Ross Muken, an analyst with Evercore ISI. While health tracking isn’t a new concept, putting that data into an algorithm to help change behavior and get ahead of a health crisis is the next big frontier for wearable health technology products. Experts caution, though, that while the FDA “cleared” these new apps, it hasn’t actually “approved” them, which is a bureaucratic distinction that means they haven’t faced as much rigorous testing as something that has gained the agency’s formal OK. For example, there are no findings from studies or trials that offer evidence of the fall prevention or ECG apps’ benefits, Topol said. “We don’t have any data to review. These are unknowns.” Someday, he added, he expects the “medicalized smartphone” to be more common, cheaper and accessible to seniors. Right now we’re seeing the very beginning of this technology be put into use. “Technology is way ahead of medical practice,” Topol said. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

High-Deductible Health Plans Fall From Grace In Employer-Based Coverage

Jay Hancock, Kaiser Health News With workers harder to find and Obamacare’s tax on generous coverage postponed, employers are hitting pause on a feature of job-based medical insurance much hated by employees: the high-deductible health plan. Companies have slowed enrollment in such coverage and, in some cases, reinstated more traditional plans as a strong job market gives workers bargaining power over pay and benefits, according to research from three organizations. This year, 39 percent of large, corporate employers surveyed by the National Business Group on Health (NBGH) offer high-deductible plans, also called “consumer-directed” coverage, as workers’ only choice. For next year, that figure is set to drop to 30 percent. “That was a surprise, that we saw that big of a retraction,” said Brian Marcotte, the group’s CEO. “We had a lot of companies add choice back in.” Few if any employers will return to the much more generous coverage of a decade or more ago, benefits experts said. But they’re reassessing how much pain workers can take and whether high-deductible plans control costs as advertised. “It got to the point where employers were worried about the affordability of health care for their employees, especially their lower-paid people,” said Beth Umland, director of research for health and benefits at Mercer, a benefits consultancy that also conducted a survey. The portion of workers in high-deductible, job-based plans peaked at 29 percent two years ago and was unchanged this year, according to new data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.) Deductibles — what consumers pay for health care before insurance kicks in — have increased far faster than wages, even as paycheck deductions for premiums have also soared. One in 4 covered employees now have a single-person deductible of $2,000 or more, KFF found. Employers and consultants once claimed patients would become smarter medical consumers if they bore greater expense at the point of care. Those arguments aren’t heard much anymore. Because lots of medical treatment is unplanned, hospitals and doctors proved to be much less “shoppable” than experts predicted. Workers found price-comparison tools hard to use. High-deductible plans “didn’t really do what employers hoped they would do, which is create more sophisticated consumers of health care,” Marcotte said. “The health care system is just way too complex.” At the same time, companies have less incentive to pare coverage as Congress has repeatedly postponed the Affordable Care Act’s “Cadillac tax” on higher-value plans. Although deductibles are treading water, total spending on job-based health plans continues to rise much faster than the overall cost of living. That eats into workers’ pay in other ways by boosting what they contribute in premiums. Employer-sponsored group health plans, which insure 150 million Americans — nearly half the country — tend to get less attention than politically charged coverage created by the ACA. For these employer plans, the cost of family coverage went up 5 percent this year and is expected to rise by a similar amount next year, the research shows. Insuring one family in a job-based plan now costs on average $19,616 in total premiums, the KFF data show. The American worker pays $5,547 of that in a country where the median household income is more than $61,000. The KFF survey was published Tuesday; the NBGH data, in August. Mercer has released preliminary results showing similar trends. The recent cost upticks, driven by specialty drug costs and expensive treatment for diseases such as cancer and kidney failure, are an improvement over the early 2000s, when family-coverage costs were rising by an average 7 percent a year. But they’re still nearly double recent rates of inflation and increases in worker pay. Such growth “is unsustainable for the companies I have been working with,” said Brian Ford, a benefits consultant with Lockton Companies, echoing comments made over the decades by experts as health spending has vacuumed up more and more economic resources. For now at least, many large employers can well afford rising health costs. Earnings for corporations in the S&P 500 have increased by double-digit percentages, driven by federal tax cuts and economic growth. Profit margins are near all-time highs. But for workers and many smaller businesses, health costs are a heavier burden. Premiums for family plans have gone up 55 percent in the past decade, twice as fast as worker pay, according to KFF. Employers’ latest cost-control efforts include managing expenses for the most expensive diseases; getting workers to use nurse video-chat services and other types of “telemedicine”; and paying for primary care clinics at work or nearby. At the “top of the list” for many companies are attempts to manage the most expensive medical claims — cases of hemophilia, terrible accidents, prematurely born infants and other diseases — that increasingly cost as much as $1 million each, Umland said. Employers point such patients to the highest-quality doctors and hospitals and furnish guides to steer them through the system. Such steps promise to improve results, reduce complications and save money, she said. On-site clinics cut absenteeism by eliminating the need for employees to drive across town and sit in a waiting room for two hours to get a rash or a sniffle checked or get a vaccine, consultants say. Almost all large employers offer telemedicine, but hardly any workers use it. Thirty-nine percent of the larger companies covering telemedicine now make it comparatively less expensive for workers to consult doctors and nurses virtually, the KFF survey shows. This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.